By Cur8.art

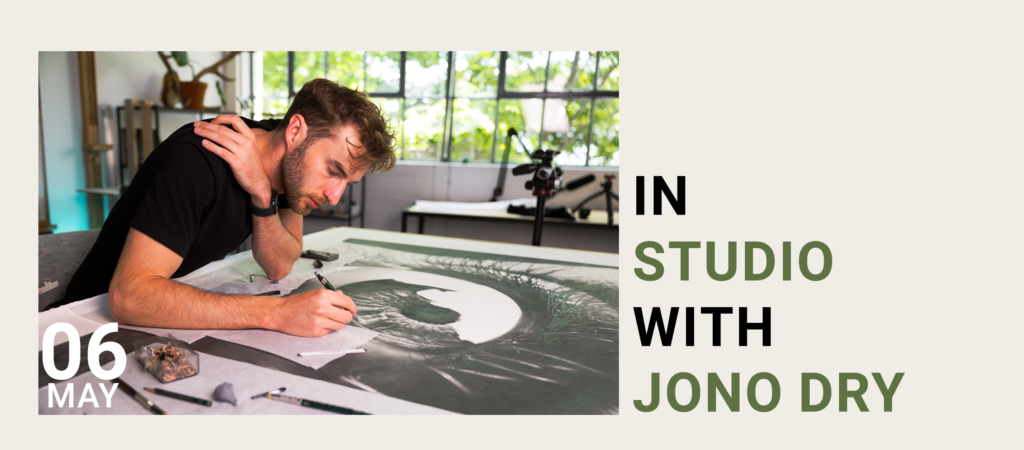

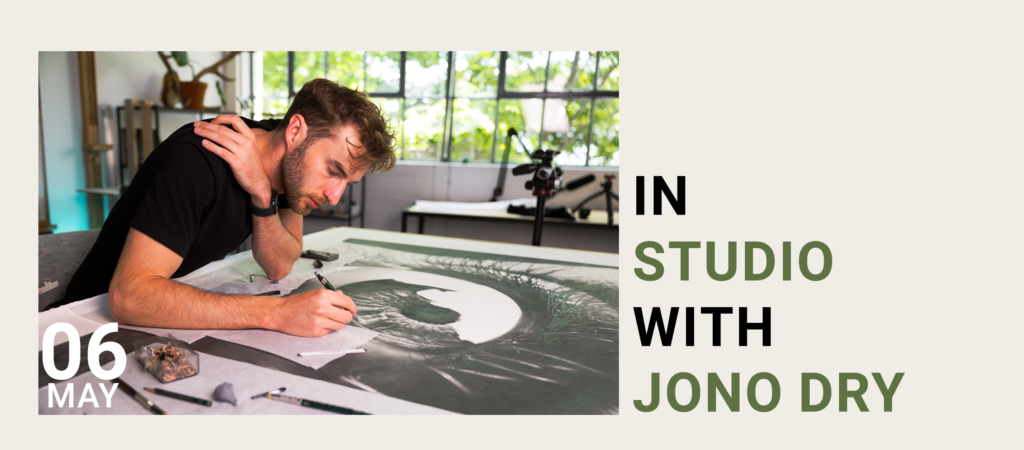

Tenacity, grit, precision. These are some of the words that came to mind when we visited Jono Dry’s studio this week in Cape Town.

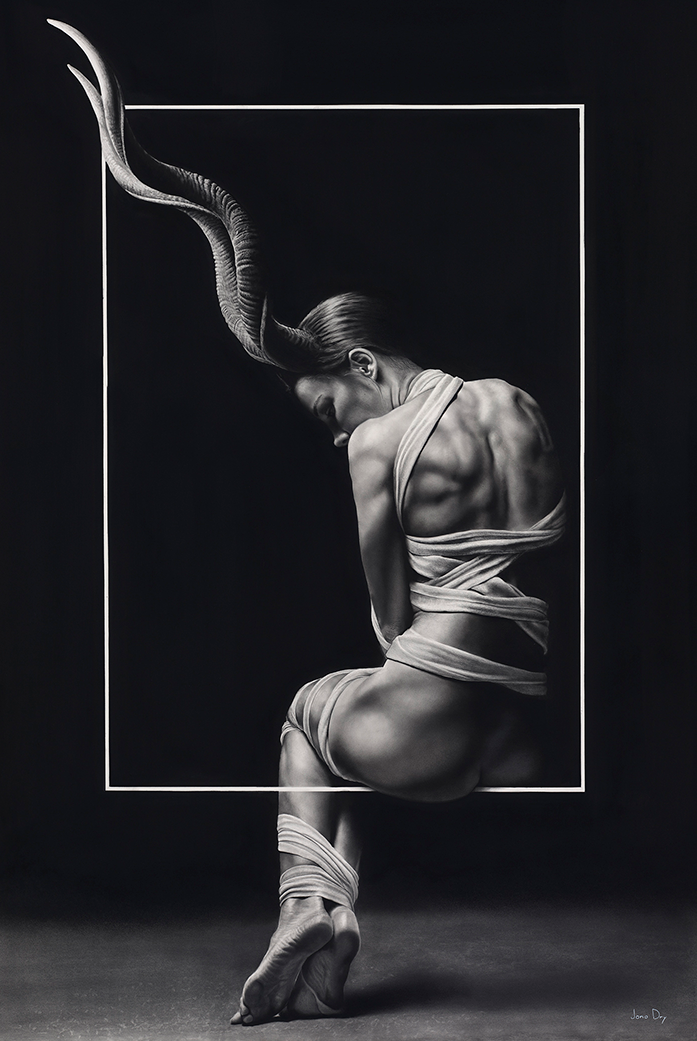

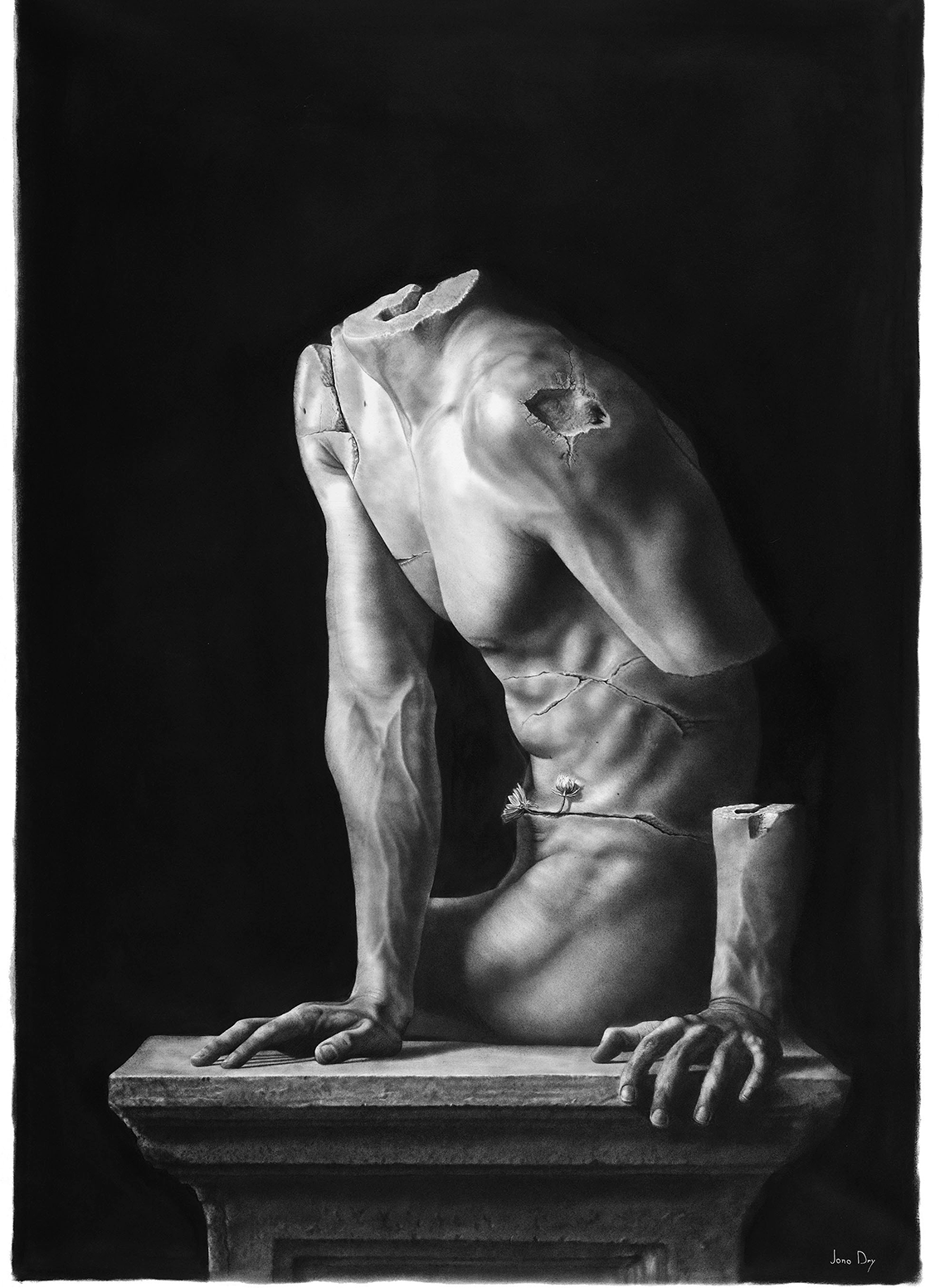

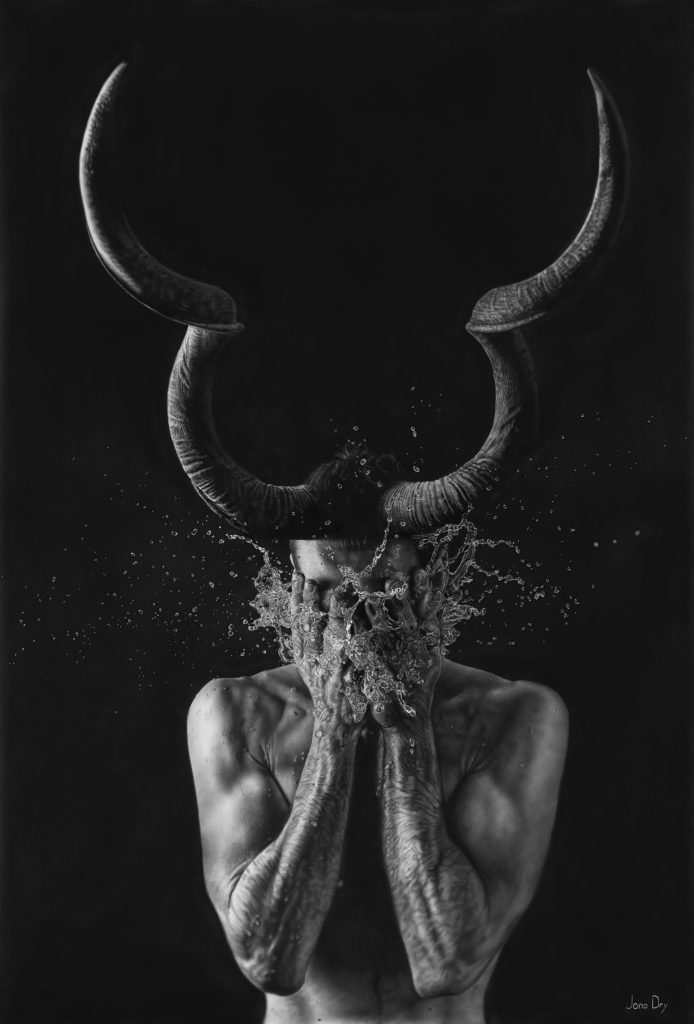

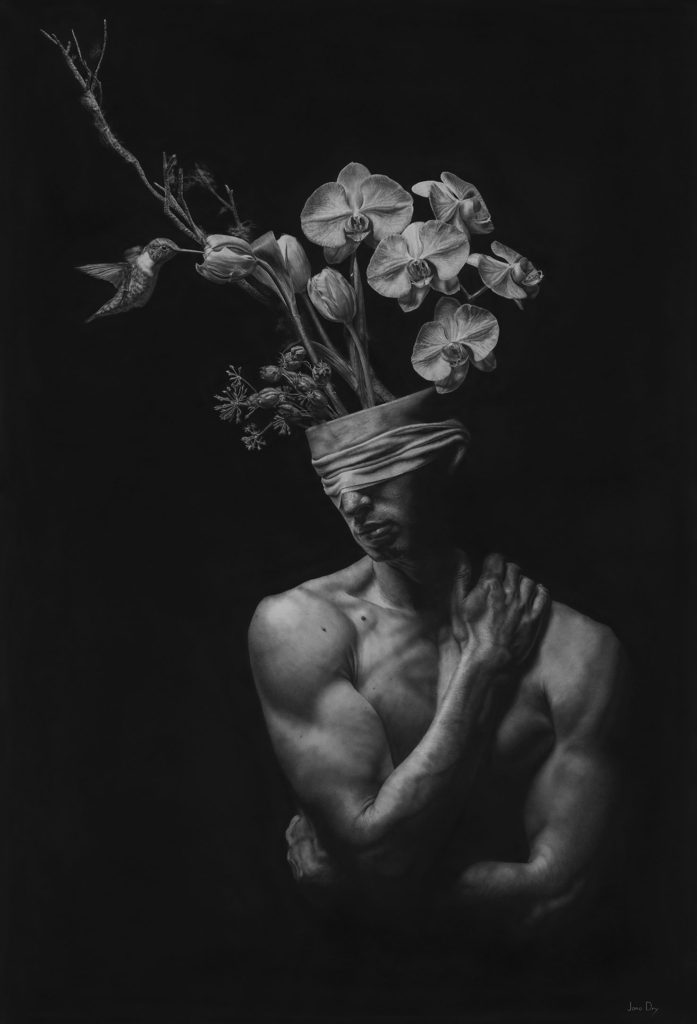

Dry, a celebrated hyper realist known for his astounding works in graphite greets us alongside his team in his light drenched, open plan studio where his large-scale drawings line the walls – which in all their hyperreal precision are nothing if not utterly engrossing. Surveying each artwork in the room, close-up and peering into the delicate strokes and smudges of graphite, I try to reconcile Dry’s articulation of a single hair – a glint of light on the muscular thigh of a figure. In the pursuit of unveiling the method behind his masterful work, we caught up with the artist on his creative practice.

You’re a self-taught artist, what has that journey been like?

I was interested in art at school and was surrounded by friends who were really creative. I chose not to study, took a gap year and I just tried to make it in Hermanus. It’s an arty town with a lot of art galleries – my mom is an artist as well. I was in the UK for a while and was quite homesick and she convinced me to come home and have an exhibition with her. From there I was just trying to kick it off and make it work. Part of it was also my dad, he thought I was going for a free ride by not pursuing anything of substance, so part of me wanted to prove him wrong in really trying to make it work. I loved drawing, and I also really loved computers so it was fortunate with timing that social media started booming as I started trying to build a career. Combining those two things and finding it very easy to research marketing online – anything that I wanted to learn I could just teach myself through the internet, and then subsequently I found that I am interested in business as well. That’s all amalgamated into a good recipe.

What are your thoughts on the often contrasting roles of business and art?

I think those two things are often at odds with each other. People view art as this romantic thing that should only be practised when inspiration strikes, but if you look at it through a business lens that’s just not viable. You need to pitch up every day, you need to come to work and grind through it even if you don’t feel like it because it’s a job. That was quite a big realisation and part of the foundation of [my work] becoming more of a business venture. It also fulfils me and stimulates me creatively but it is a business at the end of the day.

Have you always worked in hyperrealism and what drew you to the style?

Hyperrealism is the most accessible genre for appreciation. As a kid, we were all just interested in artists who were pushing the boundaries with realism – with pencil, with paint. That interested me back then and it still interests me now. I would like to branch out to more abstract, work with etching and sculpture and playing – experimenting. But again, the survival thing. Because I was practising hyperrealism and became proficient in that, that was my comfort zone. So I’m definitely in a comfortable space with that and then within that space, I’m trying to push it, so that’s where the surrealism aspects come into it. That makes it more interesting for me, I’m not just doing portraits. I find myself more on the accessible side of the fine art spectrum where it isn’t very difficult to consume my work which I think is also the reason that it’s commercially viable. I think I’m always trying to push it more toward the conceptually stimulating side just for myself as a challenging direction.

What does your day-to-day as a professional artist look like?

Day-to-day has changed over the last couple of years. When I was just supplying my agent I had a specific amount of work I wanted to try to produce a year to financially hit my goals. Life back then was wonderful and simple. The phase of composing an artwork would include arranging photoshoots, having conversations with friends about concepts and trying to put together a composition that would be stimulating. When I’m not in the planning phase, day-to-day would just be coming to the studio and drawing till five and fighting the urge to be distracted and procrastinate. So that’s how things were around 2019 and then with Covid and disruptions things moved around, but I also started doing Youtube and exploring different avenues of expression. I didn’t have enough time to draw, shoot and edit all my videos as well as manage the staple prints so I hired some help, releasing that control and giving someone else that agency. Letting go of control is a very difficult thing in itself but it’s also crucial and fundamental to expanding the business. And it allowed me to think about new pursuits and to build new things. I’m surrounded now by people who are working with me to build something together which is fulfilling and incredible. So my day-to-day has changed from just thinking about drawing, to coming in and speaking to the team and figuring out how we want to plan the next month and strategies for posting schedules and for content and for other artists we might be working with. Then I’ll be able to maybe draw around that so I’m trying to find balance and the ideal is somewhere in the middle.

Can you walk us through your artistic process? What initially sparks an idea for a drawing?

I have this belief that there are a ton of ideas floating around in the ether and we all have access to them, so if an idea comes around then I would usually write it down and email it to myself. From there start chatting to friends, in this case, my team and chew it out and figure out how aesthetically it would work, if it’s stimulating and for what reason I want to do it. So starting a visual concept and then seeing how can we practically make that happen. Seeing how we can take references and put together a composition practically first in Photoshop. We will photograph and then Photoshop everything into position and then that will either involve bringing models, setting up the studio and then doing a shoot that way or just doing a smaller shoot in the studio with objects. Once the composition is together I will probably put together five to six ideas and run those by my mom, the team and a ton of friends – just getting loads of opinions. I’m a big fan of spreading the load and getting multiple minds in on one idea. Once it’s decided I will wet my paper, stretch it and start rendering out the drawing.

You’ve spoken of mental health as a theme that runs through your drawing. With a practice that requires so much patience and energy, do you find your work cathartic?

There is a catharsis in working in hyperrealism. Because the nature of my work is more meditative, I’m spending a lot of time in my head and so trying to navigate that space and trying to understand myself is what I spend most of my time doing. While drawing, a lot of that time I’m not all there and the things that are happening around me affect that space. I found that a way to be more efficient in my work is to take responsibility for my headspace as much as possible – and subsequently, that started informing my work as well. So works like Discomposure, I was very conscious of the transitional space I was in at that time and that inspired the artwork. Another aspect of my work is loneliness and that’s been a huge thing throughout my life and the predominant struggle that has been represented in my work.

How long does it take to complete one of your large-scale drawings?

On average about two months. The one drawing, Pupil was three two-month stints over a year and I had to take breaks because it was too intense. I find it’s more efficient to create larger works because they have a presence.

Do you work on one drawing at a time?

Yes, I’ve tried to work on multiple pieces at a time but I’ve never been able to.

You’re very open to sharing your work and process with others online through Instagram and Youtube – what do you hope people will gain from engaging with your practice?

Sharing is a way of combating loneliness. I think anyone producing work, we inherently have this idea of wanting to share or being afraid to share. And even if you’re afraid of sharing that’s kind of indicative of that being the goal, of that being the thing that you want to avoid or the thing that you want to be able to do one day. So that’s the first step, to be able to share something that I’ve been working on, be proud of it and sometimes if I’m lucky someone will be moved by the work. Then a few levels down from that will be sustainability, just sharing my work with people who are viewing it and enjoying it also helps me to be able to produce my work in a very practical sense.

The art scene has evolved online since you began your accounts on Youtube and Instagram. How have things changed for you?

Things have changed with the way that things are marketed. Images were the way to share things and now they are going to video. I have always been producing videos, but I never thought I’d be able to marry the two. Being able to tell a story through video is a lot easier than a static image. Now that video is a really powerful way of marketing and sharing it’s become a challenge to find stories within my practice and to think about what I’m doing. I know some people who want to do a similar thing and being able to be as honest and transparent in that space turns out to be valuable to other people. I continuously struggle though, I don’t want to share too much of myself personally and to try to keep those two things separate is quite difficult. We’re all voyeuristic in a way. We want to have that insight into other people’s lives. Sometimes I do feel like I’ve been overexposed and then I’ll go back into my shell and try to recuperate. With the video stuff I had to put myself out there personally, my voice and who I am, that has been a challenge and I’ve been grateful for the whole experience.

Who are some artists on your radar at the moment?

Jeremy Geddes, Miles Johnston and Pamela Bentley.

Dead or alive – who is an artist you would love to meet?

Zdzislaw Beksinski and Judith Mason.

Do you listen to anything while you are working – music, podcasts?

Mostly audiobooks, but also podcasts if there is something good coming out. So the story behind the audiobooks is that I am mildly dyslexic and there is a lot of anxiety around reading for me. It’s been quite a huge sadness for me and when I started listening to audiobooks – that’s been an entry into a world that I didn’t think I was going to have access to and now one of my biggest passions is literature. I will consume almost anything and I’m not fussy, I will read complete trash and then read something that’s quite dense, I am easily entertained there.

What would you identify as the essential tips for an artist?

I think one issue for a lot of artists is that they don’t sit down and produce the work, they procrastinate because it’s hard. It’s really difficult to get yourself to produce art and then the next barrier which is also hard is to show people. Once you’ve made something to show people is important. I’m sure there’s a Maslow‘s hierarchy of this in a way like you have to have art to show people and then the next thing is to show people. Maybe before you even have art to show people the work should be honest as well. So it’s hard to know what exactly the single most important thing is. There is a psychological aspect of the question and then there’s also a commercial aspect, and so if you’ve got artwork to show marketing is everything.

Do you think art makes the world a better place?

I think it’s a mirror. For a person to grow they need to look at themselves and for a culture to grow they need to look at themselves and so artists mirror those people. So directly in the moment that’s why it’s good for the world. Past that point it’s history, it’s an archive. It’s a way of capturing pain, suffering, joy, achievements and celebration and that’s why in wars people target sculptures and art collections. It’s an incredibly powerful tool to document our experiences.

What is the role of an artist?

That I think is to try and be as honest as possible. That is when people can connect. It’s the same with comedy as well. Really good comedians are sharing honest experiences of their lives and that’s when it’s not trite. Something novel is like when someone does an honest take on something that is happening currently and we celebrate that and I think the same applies to art.

It is most certainly this continuous search for honesty that has us so moved and so connected to Jono Dry’s drawings. Confronting an artwork often comes with the expectation of feeling or sentiment, and like Narcissus who fell in love with his own reflection, we can be consumed by a work of art – a mirror of ourselves, our lives, our history.

For enquiries on works and prints visit Jono Dry Art.