By Cur8.art

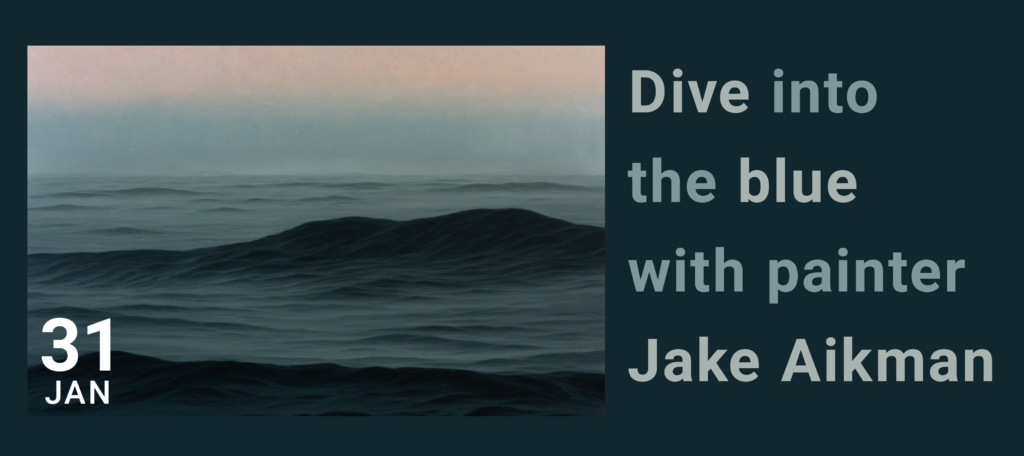

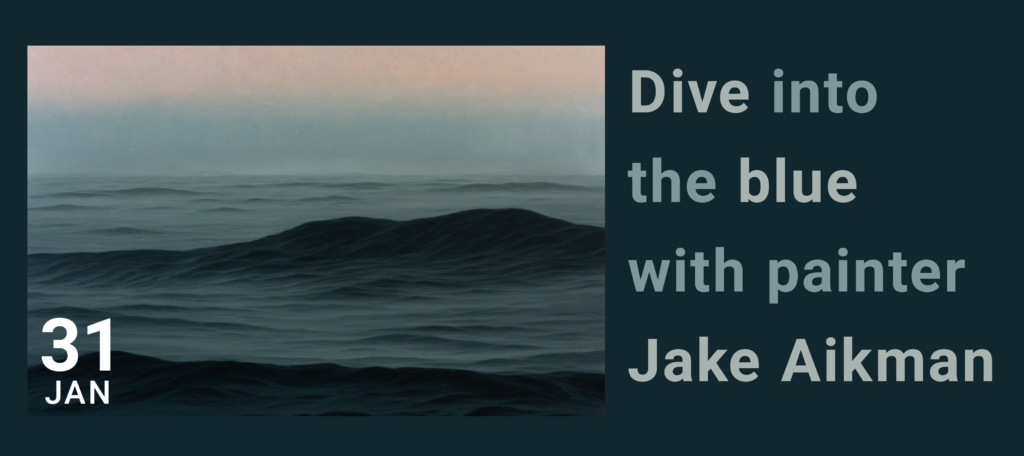

The ocean is an uncomplicated swirling abyss waiting to swallow eager swimmers that dare to jump in. It is here in the sometimes still, sometimes moving bodies of water that artist Jake Aikman finds his subject matter. Visiting the artist (and surfer) in his Woodstock studio in Cape Town, we dived a bit further into his preoccupation with the sea and the fascinating journey which has led him to his practice today.

Take us back to your beginnings as an artist. When did you first begin painting?

I was living in St James, I had come back from overseas doing various odd jobs like farm labour, coffee jockey… I was working at a muffin bakery/coffee shop in Wales. When I got back to South Africa I was at a loose end. I found a job at Olympia Cafe. It was up-and-coming and very exciting so I went there and spent a couple of years cooking and I worked my way up. I thought I might become a chef. There was always art on the walls, artists bringing things in to show. There were a couple of local Kalk Bay artists, Ben Coutouvidis, he lived up the road, and Hermann Niebuhr. They were friends. They offered some lessons and I assisted them in their studio. It got me excited about painting again because I hadn’t picked up a brush since high school. I hung some work in the restaurant, they sold – I thought this was exciting. So that got me away from cooking, which was starting to feel like a grind, it was an extremely demanding environment. I applied to art school, it seemed viable. I had resisted an art career. It didn’t appeal to me when I was 18. The struggling artist trope didn’t align with me teenage sensibilities. I needed to work to buy a car that could get me to the surf.. but once I kind of had a little bit of an idea that there was potential for commercial success So I applied and got into Michaelis and quickly got frustrated with the thought of having to be re-educated. I thought that I knew what was going on, I could paint but I didn’t know a thing about the art world and potentially where I could go, so it was humbling to be taken down a few rungs, to being a student and having to write and do all the kinds of things that I dreaded after leaving school. I ended up being there for seven years, but I was fortunate enough to be taken up by Everard Read gallery before I started my Masters. My fourth-year work was exhibited as a solo show at Everard Read Cape Town, which made it financially viable to continue studying. I was a bit older than the others and so I thought if there was an opportunity to get my masters before I’m 30 I have to get it right now rather than take time out and think about it. It was worth it to take the next step. Stephen Inggs was my supervisor, and he nurtured and pushed me to think more deeply about what I was doing, and I made a significant move away from photo-realism.

Courtesy of Suburbia Contemporary.

Courtesy of Suburbia Contemporary.

Your work seems to move between the boundaries of abstraction and realism, what continues drawing you shift between the two?

As an undergrad I was very much dependent on photography. My idea of good paintings were paintings that trick people into thinking that they’re looking at a photograph. For me, that was the highest praise then. That kind of virtuoso painting, I realised, wasn’t necessarily getting to the core of what I wanted to say; it was almost something I could hide behind. It had a structure or framework that grounds the viewer. At the core of what I was trying to convey was an instability, in terms of my subject and where I wanted the viewer to be positioned. I now view the abstract work of artists that dive into that uncertainty as brave. My partner Alexandra Karakashian has taught me a lot about moving in that direction through her work.

I’ve moved away from feeling the need to have representation literally, but I don’t see what I do as abstract. They are kind of loose impressions of the same subject, so they’re still landscapes and seascapes… but they’re not strictly abstract, they are loose versions of the same thing. I’m happy that I managed to embrace both modes of painting (realism and loose interpretations) in my practice because it’s also about your body. Your body winds up when you’re working with certain movements and to be able to break away from that in moments is freeing..

What do you want people to experience when looking at your work?

Uncertainty. I think that’s it. That would be the kind of overarching idea – with whatever they bring to that, or whatever is provoked in that. For me, as the painter, we fail if someone arrives and is like “Ah, it means this, it’s done”… I want them to think about their world, the world at large.

What is your reference to the ocean?

Well, I surf so I’ve spent a lot of time in the sea – well not enough at the moment (laughs). The painting has never been about the deep sea, they’re always in some kind of proximity to land and I have done ones where there are islands and land masses in the distance to heighten that uncertainty. Am I standing on a jetty where there’s water or am I out at sea? I suppose when I’m bobbing around on a surfboard I’m not far enough out to be lost at sea, so it’s about capturing that middle ground. And the sea provides a meditative space, it’s not telling you about any specific place. The “placelessness” is important and what I would like the viewer to experience. Ownership is taken away. Whereas land is more complicated.

What does your day-to-day as a professional artist look like?

I don’t get to the studio very early, but I try to get back in a bit later in the day, especially over this last year with a baby, we just kind of shuffle things around her. I try to get five hours of solid painting per day.

What materials do you use?

At the moment I’m working on linen that is clear primed. It’s got quite a strong tooth. For quite a few years I painted on white primed materials, but for the last year or two, I’ve been working with the natural colour of the linen, it’s receding, and it adds to the depth of the painting.

And board?

The Seascape Aggregate series started with a wooden board next to my palette that I was applying all the leftover paint onto. It was 2016/2017 that I started to see something I liked about this scrap piece of wood that had the leftover paint and I started to build it up and it started to form an image that I thought was quite pleasing. So, that was the first of Seascape Aggregate, which is essentially paintings formed from whatever is happening in the other paintings. They take a lot longer to do. I don’t set out to paint them so they evolve, it’s a process. There are about ten other paintings before I can arrive at that painting. But I think that’s also where their strength comes from…Those paintings embody a collection of works.

How long does it take to complete one of your works?

A lot of people want to know that. They normally want to know that with regard to a larger seascape work, that looks very labour-intensive. Some of the works that appear more laboured have gone quickly and smoothly, and other works that have given me more trouble, I put them aside. I usually have at least 5 unfinished paintings on the go. Some I’ve worked on for a year, another for four, which I aim to finish this February…

Can you walk us through your artistic process? What initially sparks an idea?

I start with some photographic references, I will find something compositionally and then I will shift things around, but I don’t sit with photographs and paint, I used to – I would sketch them out with paint. [With the mural painted in Kyiv for ArtUnitedUs] I had to square out the painting as it was roughly about 13m, you can’t see it when you’re against it.

The trouble with working from photographs…

You want the painting to work as a painting and often looking at photographs, they don’t work as paintings, if you strictly adhere to what the water is doing in a photograph it works as a photograph because you look at it and go “oh this peak on that wave is happening”, but if you paint that little pointy thing on the end of the wave it looks ridiculous in painting. You have to change it and make it your own.

What advice would you give to artists trying to break into the industry?

If it is your passion then you persist and pursue it. There are so many different avenues, there’s no set path. Sometimes it happens (whatever success looks like to you) to people in their 20s and sometimes in their 60s, and that can be scary. That’s what put me off as a teenager wanting a car, and why I came to it a bit later. Because it is daunting out there, there isn’t a direct path – you don’t just get the internship, get the degree, etc. There is no step ladder, no direct route and that’s why it’s tricky to give advice because for me this happened and then by some fortunate event this person was there that said: “oh I like that why don’t you…” – it really can be seemingly random. Take a shot in the dark and hope for the best, but persistence – as well as being open to those things you find difficult. The thought of writing an academic essay when I was 24 [was horrible]. But with those essays, it didn’t matter if they failed or if they were any good. I struggled with the material, the subjects, the artists and the things we were looking at, but it opened my mind to a wider view of what art could be.

Finding space for contemplation in the expanse of the sea, Aikman’s thoughtful depictions of water resonate with us all as we tether our memories to each swelling wave. Looking forward, Aikman will be showcasing work at the upcoming Investec Cape Town Art Fair this February with Suburbia Contemporary as part of the Main Section of the fair.