Nita Spilhaus was born in Lisbon in 1878 but raised in Lübeck, Germany by her grandfather. She moved to the Cape at the age of 29 where she quickly became part of a group of early ‘Cape Impressionist’ painters, including artists such as Ruth Prowse and Hugo Naudé. Spilhaus was drawn to painting in plein air where she could capture light and movement with her loose and gestural brushstrokes.

This work presents a subject that the artist felt passionate about; trees. In this lot, Spilhaus captures the dappled light as it shines through the forest canopy and illuminates the tree trunks in the foreground. There is a sense of movement in the work with her animated brushstrokes and her use of paint, applied in overlapping strokes of colour – the contrasting orange and blue paint providing a sense of depth as the viewer retreats into the background of the forest. The composition of the painting is composed of juxtaposing vertical lines accentuating the height of the trees.

Bettie Cilliers-Barnard was born in the Transvaal in 1914 and her work was exhibited for the first time in the mid-1940’s – her earlier style was characterised by a conservative realism popular in South Africa at the time. Only later on in her artistic career, do we see the introduction of abstracted forms and her characteristic use of flat planes of colour. This particular lot, dating from 1972, portrays a harmonious composition of the artist’s flowing lines, abstract figurative forms and juxtaposing colour planes. Esmé Berman explained that “Bettie Cilliers-Barnard [had] an especial fondness for the softer tones of orange, pink and greyish green, colours which can appear saccharine and sentimental if they are not braced by forceful structure and contrasting accents.” This statement applies particularly well to the above lot, which balances these soft tones of colour with forceful yet elegant curved lines.

The above drawing by Jacob Hendrik Pierneef of a leafless tree dates to 1910 – the same year that the artist first sold one of his oil paintings. Even at the young age of 24 years, there is a subtle monumentality to his work that can already be seen in the above study of a tree. This monumentality would become one of the most defining characteristics within his body of work.

Pierneef gravitated towards the depiction of landscapes throughout his life and he obsessively sketched shrubs and trees which he would often use at a later period within one of his larger composed oil paintings. He was particularly interested in sketching vegetation indigenous to the Transvaal where he was born. Pierneef’s work has often been described as having an “architectonic nature” with regards to the way the artist depicts the natural world. Pierneef’s strong use of line highlights another key characteristic of his work, that of the use of bold line to delineate form – for Jacob Hendrik Pierneef was above all an excellent draughtsman who expressed his artistic vision masterfully with a broad range of different mediums.

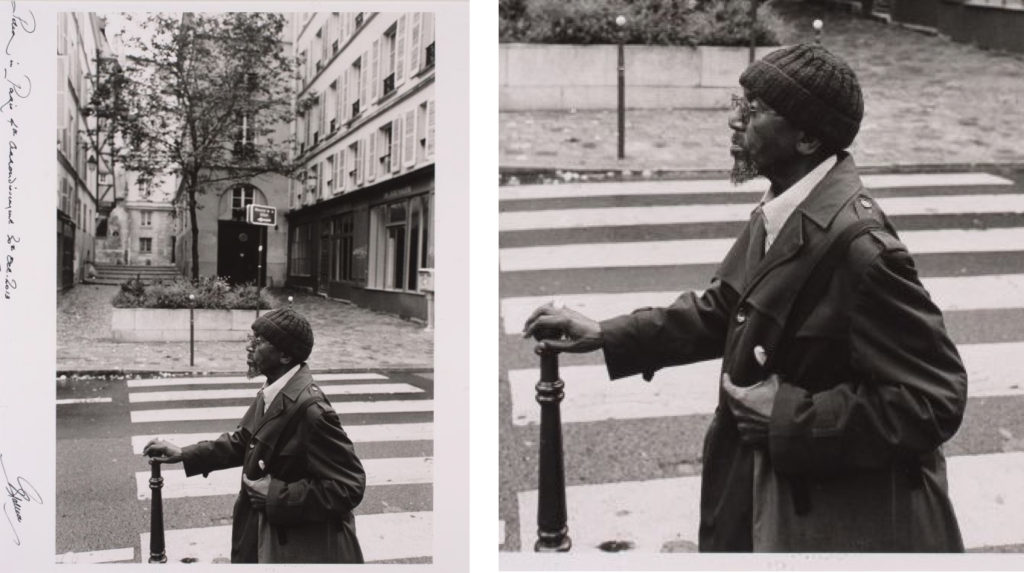

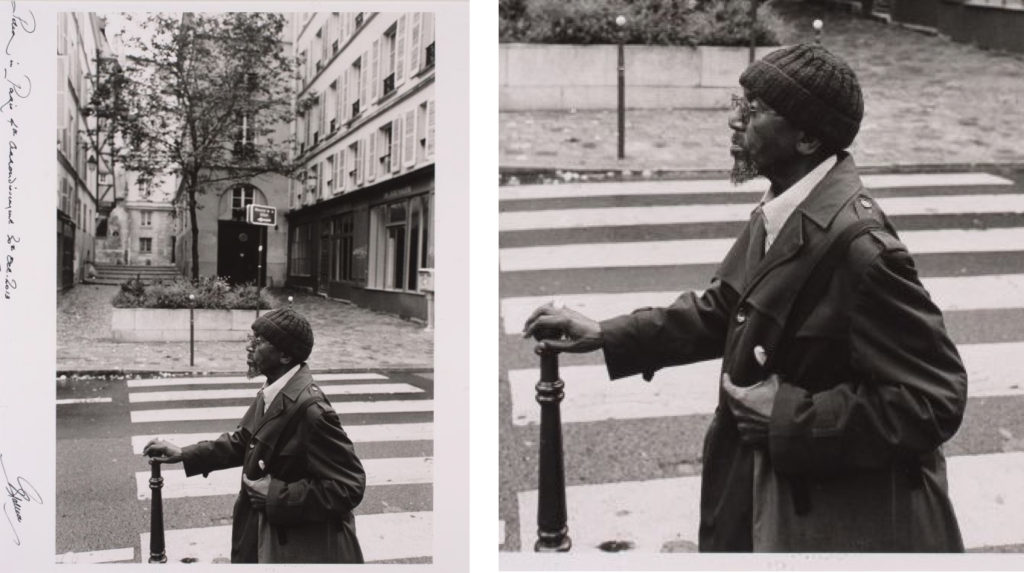

The well-known South African photographer George Hallett was born in District Six in the early 1940s. Unable to afford tertiary education, he became a self-taught photographer – Hallett once explained that he “couldn’t afford to go to university, so [his] university was out on the streets.” Hallett had a long-established friendship with artist Peter Clarke – who he met through the novelist Richard Rive.

In this lot, titled “Peter in Paris 4th Arrondissement”, Hallett photographed his friend Peter Clarke in 2013, one year before the artist’s death. The above lot captures a sense of serene timelessness – characteristic of Hallett’s photographs. In addition, there is an impression of monumentality with the juxtaposed vertical and horizontal lines within the work’s composition. The architectural backdrop and the position of Peter Clarke in the foreground, his hand resting majestically on a nearby pole, give this particular work a sense of grandeur whilst illustrating the deep respect that Hallett had for his friend.