How were the works for the show chosen?

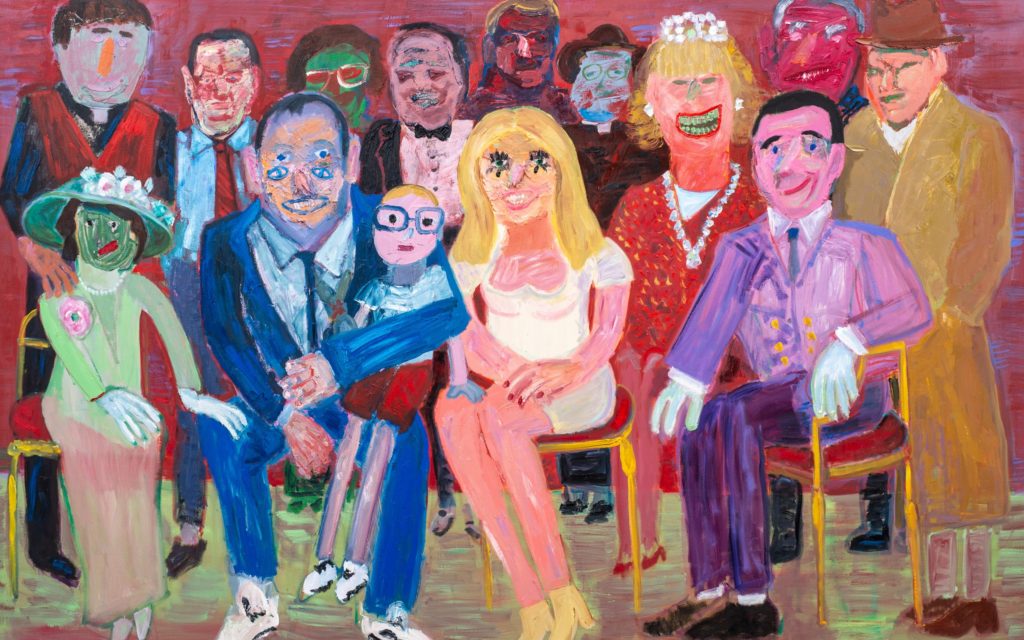

Works were predominantly chosen from local South African collections as shipping logistics informed the selection of what was available to exhibit at the show. We decided to only bring in one work from overseas, The Reunion, and it literally arrived on the day of the opening at 3pm in the afternoon. It was in Los Angeles and stuck there for two months because everything had been shut down with the pandemic. Then it went on a cross-country road trip to New York along the Route 66 where it got held up for ages by a snowstorm in New York. It did not help that it was an oversized crate weighing 700kg. It finally got on a flight to Doha as South Africa went into a strict lockdown and our borders were then shut. At that point I thought to myself ‘well, this painting now lives in Doha’. Anyways, it miraculously made it to Joburg eventually and Norval has acquired it for its collection – I don’t think it will ever go anywhere again after its arduous journeys.

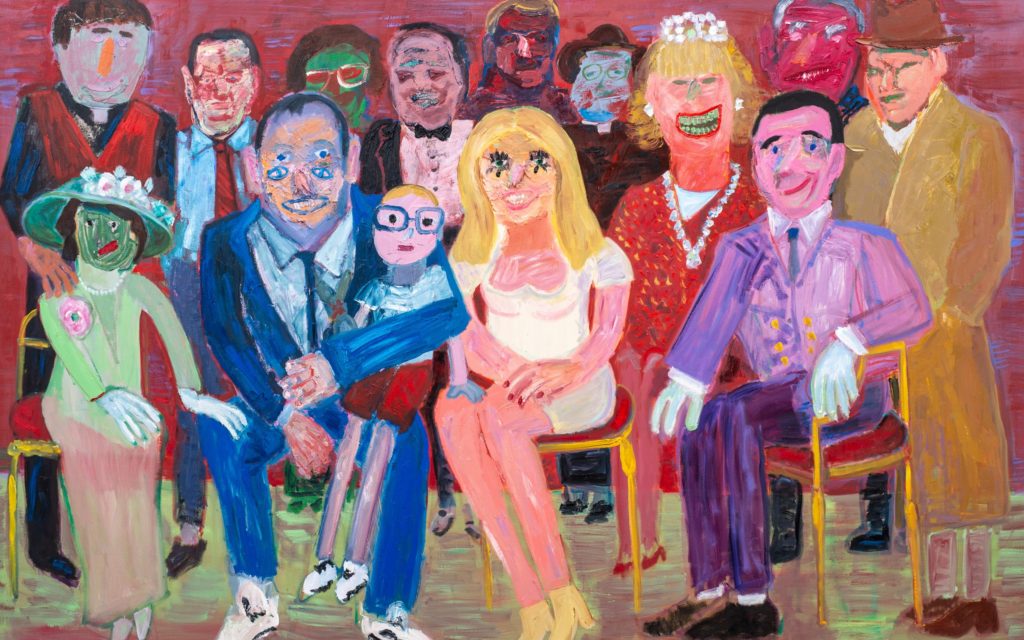

Georgina Gratrix, Tulbagh Bride, 2014

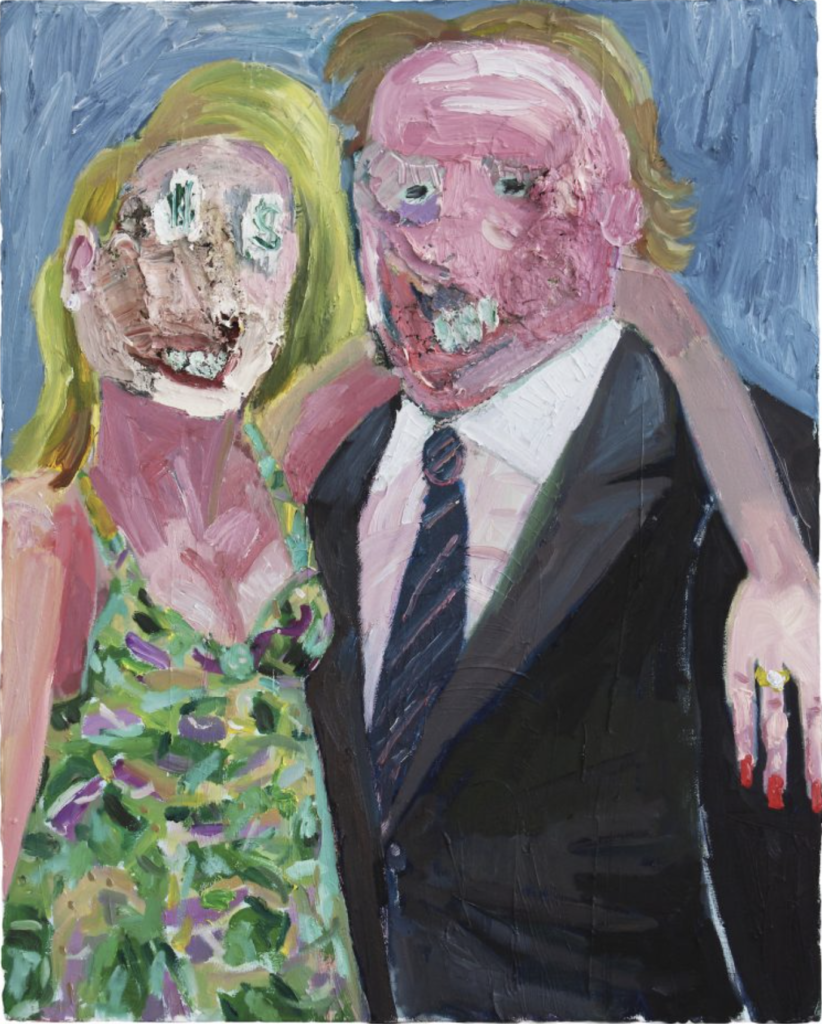

Georgina Gratrix, The Collectors, 2014

How is this exhibition different from your previous exhibitions?

This exhibition is different as Liese van der Watt gave it a framework and the show is filtered through her readings and interpretations of my work. It was interesting to see someone focus on my production and find new insights. It was not necessarily about me controlling what I wanted to say but rather allowing someone else to give a fresh perspective and reading of my work. It was more a discussion about trying to find works that Liese felt were important and works I found important – and we were able to find a middle ground. I really enjoyed working with Liese van der Watt and I realised that it was also about letting go. I have not always seen such a clear split between my figurative work and my still lives as I have always moved between both. That is why I was happy we included The Lover’s Discourse, which is a sort of bridging between the two.

What is your process for conceptualizing and creating work?

I wouldn’t say I start working from a verbal idea but rather I work within images. I would say that I work inside of pictures and see where that takes me. I do have to be in the studio to produce work though; I don’t create works at the kitchen table or in front of the TV for example. I find painting to be a very focused thing and I like the boundaries between production and creativity.

Were you able to produce works during lockdown?

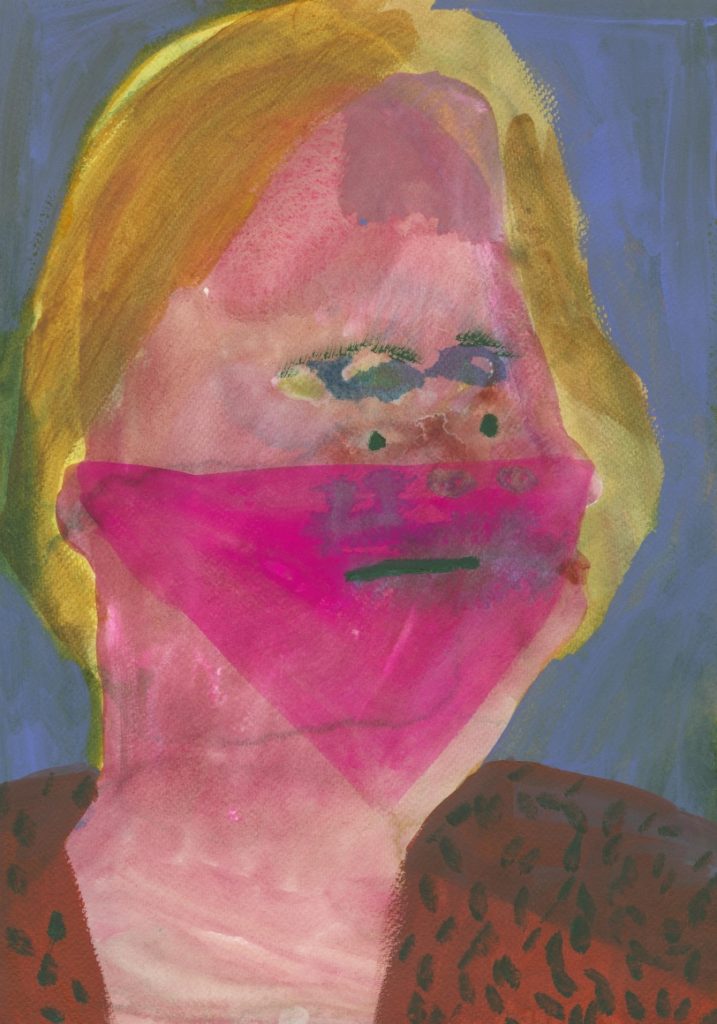

It was such a strange time. We had just come back from New York and it was as if the whole world had shifted by the time we got back. I had my studio at home and the large series of self-portraits came out of this time, 63 portraits over the 9-week period. After the initial few weeks, I decided to move on and I ended this project. These are my most recent works to feature on this show at Norval. I think that we all had to learn to adjust.

30 – 28 April 2020 (Sitting like a Pudding)

28 – 26 April 2020 (A Monologue)

How have you found the response to this show?

I really enjoyed the feedback from people that I think wouldn’t ordinarily go to art galleries, and I think that’s what I like about this exhibition; it has reached a much wider audience such as school kids and families who come to Norval for a visit. It’s very exciting to be given a platform and the important thing is to have a platform for people to engage and debate, to say I like it or I hate it or maybe that is interesting.

One of my old school art teachers from Durban came and saw the show, and then posted on Facebook about the show and people were commenting about how horrified they were – but that is quite fun actually, to still be considered provocative by making still lives, that is quite exciting. The ability to horrify with a flower painting is great.

How long have you been producing still lives?

I have always drawn flowers and doodled but what solved it for me was making them bigger, the scale did something to them. I often titled them after pop songs in the beginning; there was a fit right in the beginning where it needed to be about something more than just a still life. The scale and pushing the boundaries of colour – there is something else that they are about. It is more about picture-making. I never want to be obvious and too heavy-handed when I make works.

Has this show allowed you to see your own body of work in a different light?

It has been an important opportunity for me to re-examine and revisit my own body of work. It’s a decade of work and it’s a wild opportunity to look back and ask what am I? What am I doing or not doing? It was also interesting for me to see certain themes emerge from my body of work that have been consistent through a whole decade of work. As an artist, I have to allow part of myself to just make and for me, it’s more of a retrospective understanding when I come out of that. There is a backwards and forwards to it, a wearing of different hats. I put a hat on to make a work and put another hat on to understand it.

Did you always gravitate specifically towards painting?

I have experimented with print–making but I have always liked the directness of making something that I didn’t know where it was going to go. For me, if I know what it is going to look like, I ask myself why make it? It has obviously suited my personality because it is an isolated practice and I have always been an only child, it does not bother me to spend a lot of time alone in my studio. I like the unknown and I like not knowing what the painting will become with time.