Written by Sean O’Toole

Early success, a circumstance familiar to the acclaimed Cape Town-born painter Lisa Brice, is a psychological condition as much as a social fact. Premature success, as the writer F Scott Fitzgerald preferred to name a thing he knew intimately, “gives one an almost mystical conception of destiny as opposed to willpower – at its worst the Napoleonic delusion”. Thankfully Brice, whose star is majestically in the ascendance again, does not speak about her early years as a bright young thing in such epic terms.

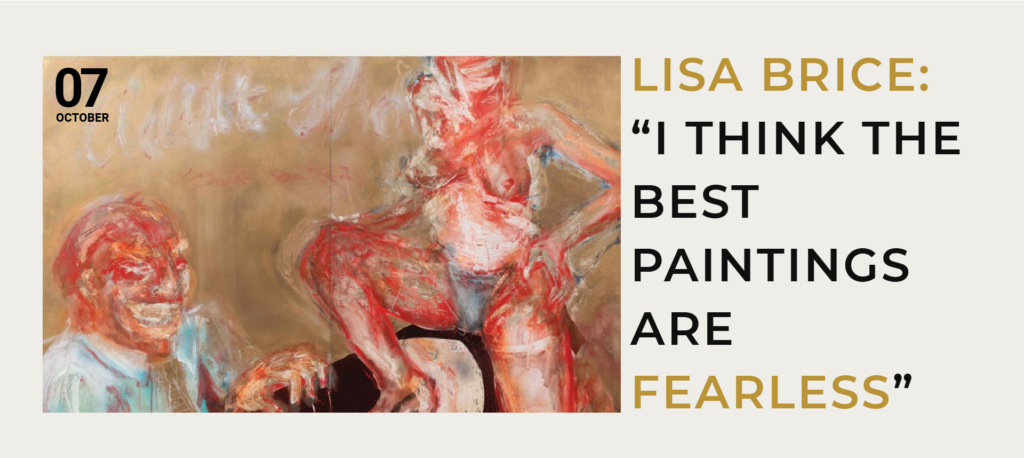

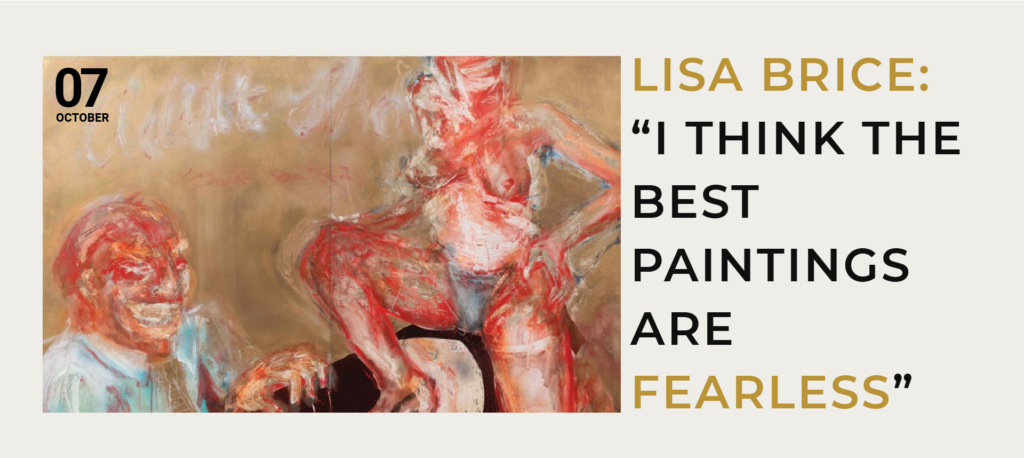

In a 2010 interview with the big-hearted Ghanaian artist Godfried Donkor, Brice simply characterised her experience of early success as unfulfilling. “I didn’t have time to develop independently,” she stated. Brice, a graduate of the Michaelis School of Fine Art, was 22 when she met German dealer Frank Hänel. Two years later, in 1993, he gave Brice her first solo exhibition in Frankfurt. Her exhibition “Sex Kittens” featured raw and fleshy expressionist paintings inspired by Thai sex workers.

Lisa Brice, Adult Show, 1992, mixed media on board, 120.5 x 169 cm.

Courtesy of the artist and Aspire Art Auctions, Cape Town

A large work from this show came up for sale at auction house Aspire in February 2020. It was briefly displayed in Cape Town. I went and had a look. Rendered in a brushy style located somewhere between James Ensor and George Baselitz, Adult Show (1992) depicts a man in a tie leering at a topless women performer. The large canvas later sold for R364 160, establishing a benchmark for Brice at auction.

It is likely to be a very temporary benchmark. News flash: Brice is a big deal in contemporary painting in Europe and the United States. Her three-metre long canvas work Smoke and Mirrors (2020) features prominently in the Hayward Gallery’s current painting showcase “Mixing It Up: Painting Today”. The work has received rapturous press, which is standard fare now for Brice. In April, Brice was feted as one of six international artists reshaping our way of seeing in How to Spend It, the influential weekend supplement of the Financial Times. Her work even illustrated the cover.

In purely mercantile terms: Brice is a growth stock. But Adult Show, and the early-career history it draws attention to, is important for more than just market trends. The work highlights career continuities, particularly with regards Brice’s attitude to the female body. Brice recently discussed this interest with curator Aïcha Mehrez. The conversation appears in the gorgeous catalogue accompanying her first museum solo in the Netherlands, “Smoke and Mirrors”, at KM21 in The Hague.

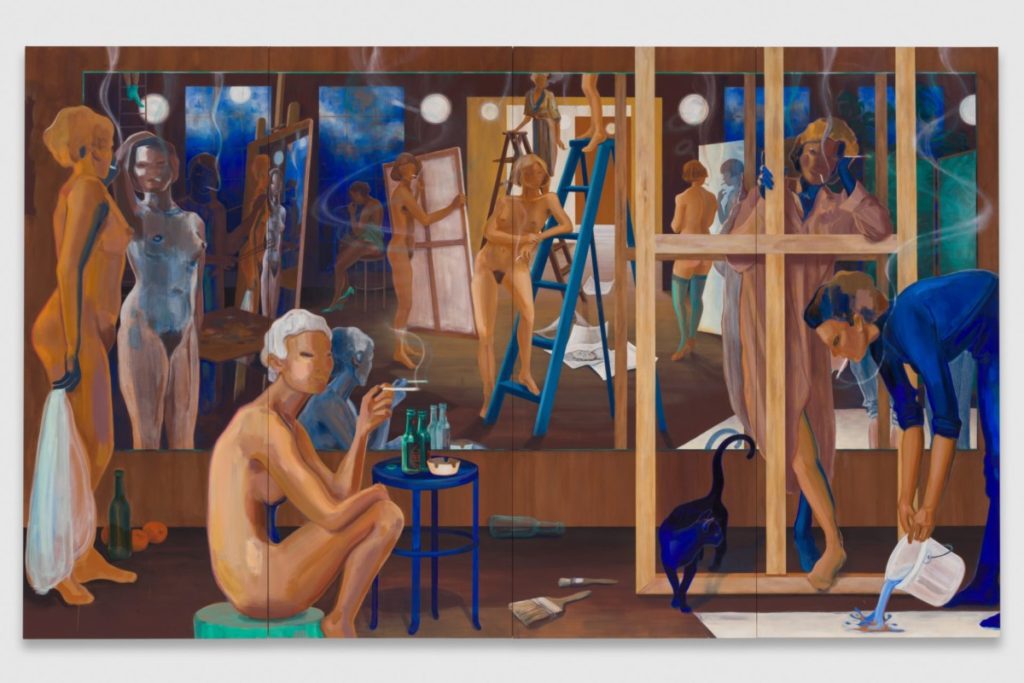

Lisa Brice, Smoke and Mirrors, 2020, ink, gesso, synthetic tempera, chalk and oil pastel and oil on canvas mounted on board, 200 x 330 cm.

Courtesy of the artist; Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and Salon 94, New York.

Photo: Mark Blower

“I am interested in how people carry and present themselves,” Brice told Mehrez. “I have recently been looking at a lot of images, either painted or photographed, of female painters throughout history. They very often appear clutching pallets and fistfuls of brushes; defensive, defiant, guarded, stern – they seem to be declaring their status within their chosen profession or calling, claiming space for themselves.”

Brice’s 1993 debut solo with Hänel was a confident claiming of space. It led to more shows with Hänel, who in 1998 published a 228-page monograph on Brice. The book compiled a decade’s worth of restless experimentation. Despite coming to prominence as a painter, Brice quickly moved on from painting, a bankable medium, to explore sculpture, installation and lens-based media. The graphically bold work she made about domesticity, privilege and violence captured the breathless, post-painterly zeitgeist of 1990s ecstatic but also anxious South Africa.

Following two more shows with Hänel, both in 1999, Brice broke with her dealer and moved to London. Although financially risky, the divorce was necessary. Commercial galleries bank on steadfastness and incremental change; they are generally poor sponsors of risk, which is what Brice wanted to experience. Rather than slot into a normalised routine of making and selling, she yearned to be in dialogue with her peers and work on artist-driven projects outside of the commercial scene.

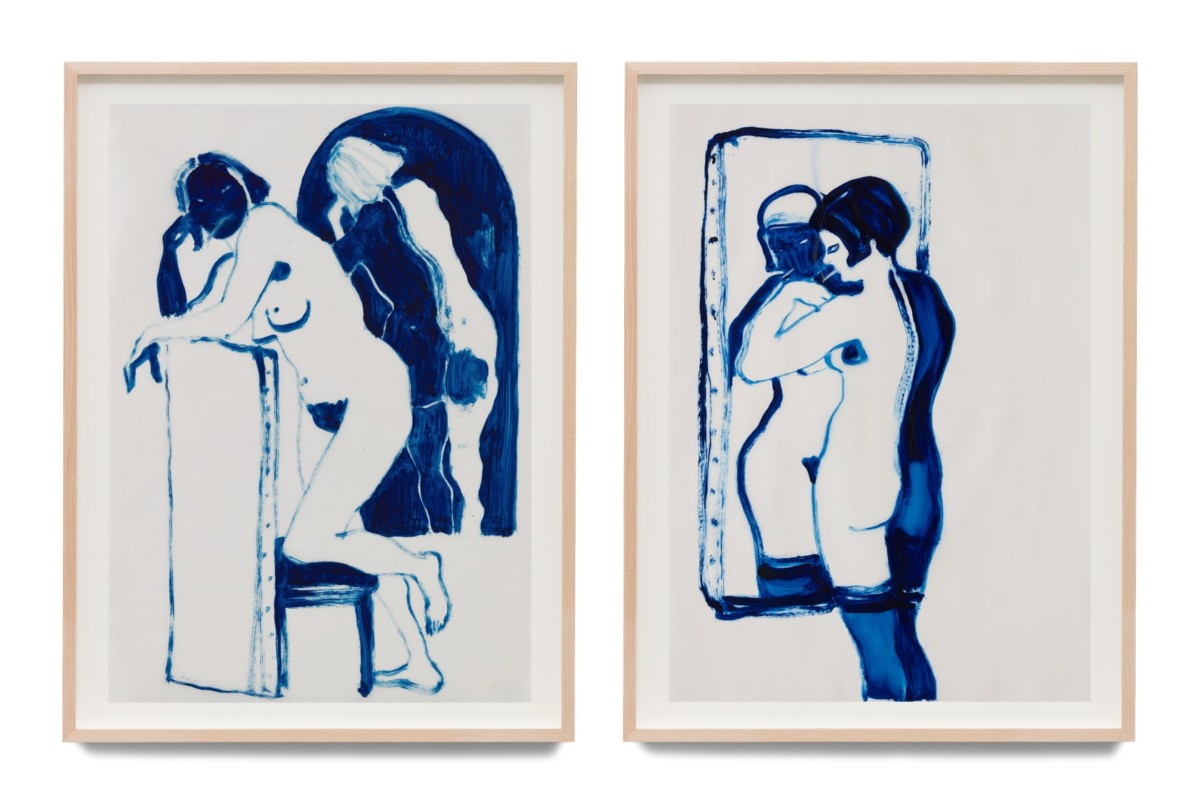

Lisa Brice, Untitled, 2020, Oil on tracing paper, each: 41.9 x 29.6cm

Courtesy the artist; Stephen Friedman Gallery, London

Trinidad, the more populace of the dual-island Caribbean nation of Trinidad and Tobago, enabled her to do just this. In 1998 Brice travelled to Trinidad to participate in an artists’ residency. She was immediately smitten, and kept returning. Trinidad holds an important place in Brice’s biography and iconography. It is where she cemented important friendships with artists Andy Miller, Peter Doig and Chris Ofili, became involved in artist-led initiatives and kept a studio.

Trinidad is also where she encountered the Blue Devil masquerade figures so much a part of the island’s Carnival of Trinidad. Originating out of slave pageants on the island’s colonial sugar plantations, participants enacting this folkloric devil figure coat their bodies in vivid cobalt blue pigment. This allusive colour has become central to Brice’s practice and greatly underpins her current visibility and acclaim.

Lisa Brice, Between This and That, 2017, synthetic tempera, gesso and ink on canvas, 198 x 244 cm.

© Lisa Brice, courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York.

Photo: Jeff Elstone

The colour featured prominently among the 86 works selected for her KM21 show, which closed in April 2021. It also dominated the various figure paintings and drawings in her recent solo exhibition at Charleston, the Sussex home of the Bloomsbury set now operating as a leading public museum. Brice did her first blue drawing in an attempt to imitate the blue light of a neon sign, which in turn prompted her to try and capture the fleeting colour of twilight.

This interest in light and chromatic intensity has been a hallmark of Brice’s work since the 1990s, but asserted itself more fully in her post-2000 paintings. Untitled E (2005), a large nocturnal scene executed dominated by palm fronds that traded hands for R250 360 at a 2020 Strauss & Co auction, is a good example of Brice’s ability to evoke mood and sense for a limited colour palette.

Lisa Brice, Untitled E, 2005, oil on canvas, 152 × 122 cm.

Courtesy of Strauss & Co

In 2014, a decade after her return to painting with the show “Night Vision” at Goodman Gallery, Brice presented a modest exhibition of eight new works at French Riviera, an artist-run space in London’s East End. The show, her first solo since moving to London, capped a lengthy wilderness period in which Brice had patiently retooled her practice. The in-your-face social commentary of the 1990s and early 2000s was replaced, in this breakthrough show, by a subtler, more introspective approach to image making. The new works repeatedly described clothed and naked female figures attending to themselves, their labours, their children and their pets.

The plucky show received little press. A visiting critic for Frieze magazine noted her “assured draughtsmanship”, preference for female subjects, habit of repetition and – perceptively – her striking use of cobalt blue. I say perceptive because Brice’s 2014 exhibition included just one ink work executed in cobalt blue. Displayed above a heating element, the untitled work presented a kneeling mother looking through a piece of gauze cloth while her infant lolls on her knee. In terms of scale and ambition, Brice poured most of her energy into two larger works. Executed in acid yellow and burnt orange on primed polyurethane film, both works depicted groups of women involved in sewing and pet grooming.

Positive press is a traditional metric of success, but in this age of ephemeral social networks an influential fan can be even more consequential. Duro Olowu is an influential fan. The London-based Nigerian fashion designer frequently posts about Brice’s work on Instagram. Olowu, who is married to the important New York curator Thelma Golden, saw Brice’s small 2014 exhibition at French Riviera, liked it, and did something far-reaching.

In 2016, for his exhibition “Making & Unmaking” at London’s Camden Art Centre, Olowu invited Brice to show a new blue painting alongside works by 69 other artists, among them big hitters such as Louise Bourgeois, Alighiero Boetti, Alice Neel and Lynette Yaidom-Boakye. Brice’s large untitled work depicting five smoking women languidly occupying an elaborately detailed interior was an immediate hit.

Lisa Brice, Untitled, 2016, gesso and tempera on canvas, 182 x 244 cm

Courtesy of Goodman Gallery

“Her extraordinary talent was finally recognised, and the important gallery invitations began to come in,” elaborates artist Sue Williamson, who first met Brice when she was a high school student in the 1980s and taught her etching. In the relatively short time between Olowu’s show and now, Brice has blown up – or, if you fancy, matched her early success with even bigger late success. Brice’s achievement is firmly rooted in her confident portrayal of women.

“Set free from the frame in which we have come to know them, Lisa’s women simply don’t give a stuff about attracting the male gaze,” says Williamson. “They smoke, sprawl, admire themselves in the mirror. Sometimes they are painters themselves. And in their carefree insouciance, they exude a power which is borne of their pleasure in their own agency, and which draws us to them in turn.”

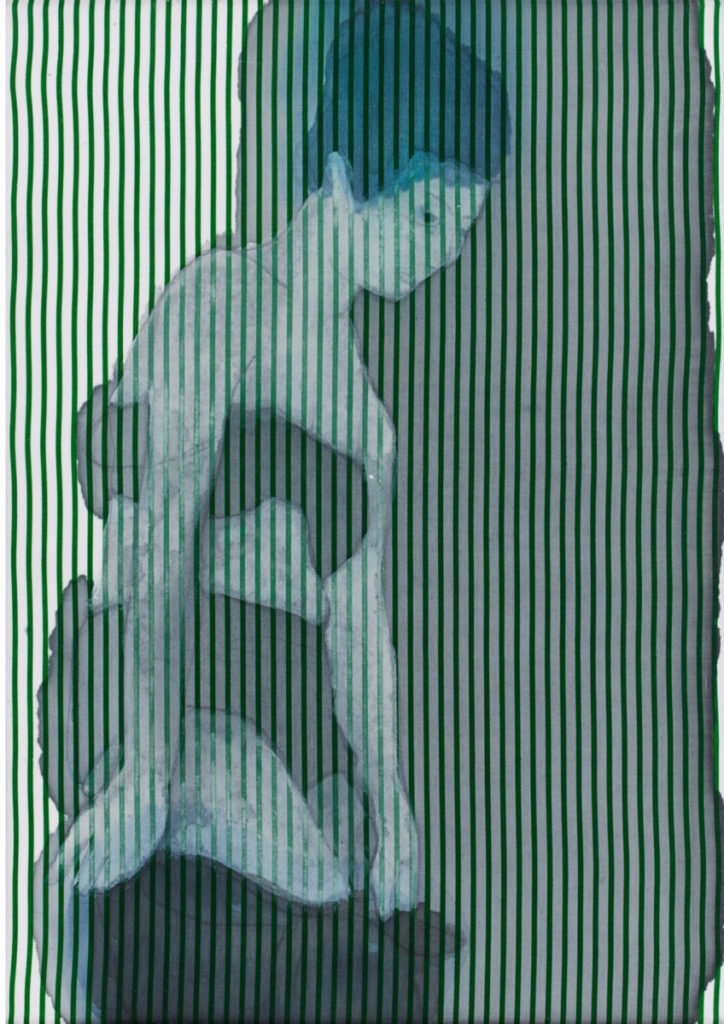

Lisa Brice, Untitled xlix, (Well Worn 14), 2015, ink on printed cotton, 42 x 29.7 cm.

Courtesy of Goodman Gallery

Lisa Brice, Untitled xlvi, (Well Worn 11), 2015, ink on printed cotton, 121 x 75.5 cm.

Courtesy of Goodman Gallery

In 2018, a year after presenting solo exhibitions in London and New York, Brice was invited to stage a solo show in London’s Tate Britain. The slot she was assigned was used to announce emerging artists, which at age 50 Brice was still perceived as in London – early success in South Africa notwithstanding, She graciously ignored the clunky frame and produced a show engaged with the female nude.

Brice is a perceptive viewer and thinker when it comes to paintings, old and new. Commenting on a nude by Pierre Bonnard, Brice in 2014 wrote how the “credible strangeness” he achieved in his idiosyncratically coloured and highly decorated works “is akin to daydreaming, being held somewhere between thought and image”. The same could easily be said of Brice’s enigmatic descriptions of female languor and assertion frequently rendered in cobalt blue. They prompt a kind of reverie, one marked by thought and pleasure at her work. But also how much she has overcome, how much she has achieved. As the artist herself last year said, “Authorship and context are after all paramount in the reading of a work.”

Sean O’Toole is a journalist and editor based in Cape Town. He is a contributing editor to Frieze magazine