Written by Sean O’Toole

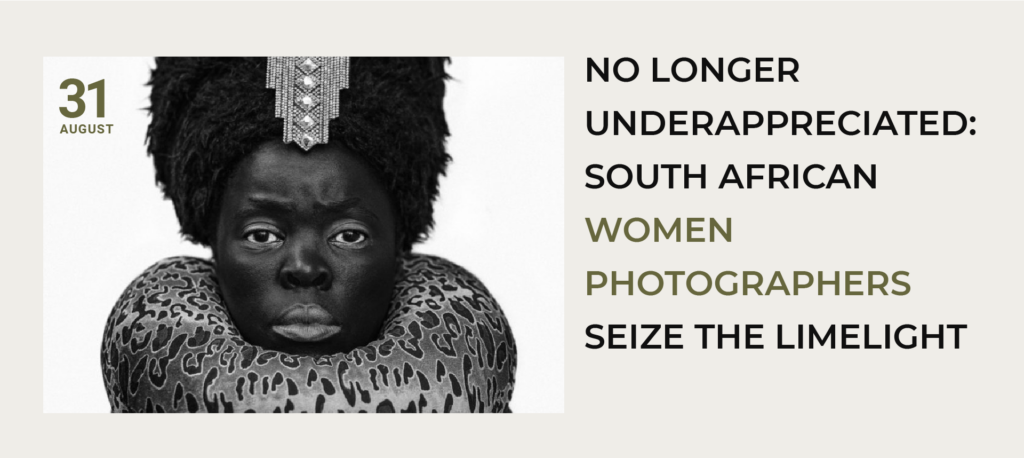

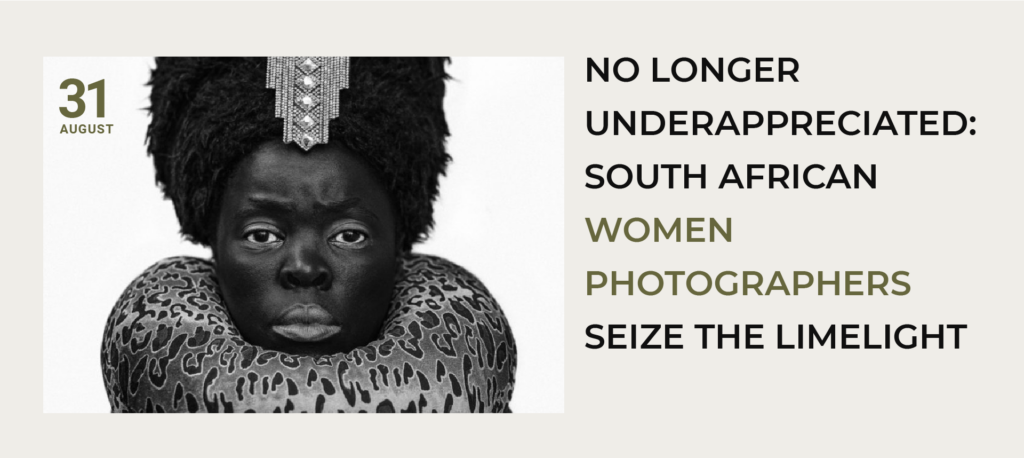

South African photography has long commanded an appreciative international audience, albeit not without certain imbalances. In the decades since Sam Haskins published Five Girls (1962), the first of his three collectable books depicting female nudes photographed in his 1960s Johannesburg studio, it has chiefly been white male photographers who have been garlanded with awards and feted with international survey shows. But in the time between David Goldblatt’s 2018 Centre Pompidou retrospective and now, things have changed. Irrevocably? Who knows, but in this time of reform and reinvention in the art world, South African women photographers are now increasingly dominating the limelight.

Women photographers are increasingly winning prominent awards, showing in ritzy museums, publishing photobooks with benchmark publishers and entering hallowed collections. I’ll get to their prices later. Notable achievers include Zanele Muholi and Jo Ractliffe, two prominent mid-career photographers whose practices were surveyed at London’s Tate Modern and the Art Institute of Chicago respectively. In June, a few weeks after Muholi’s survey closed following a six-month run, Lebohang Kganye was awarded Grand Prix Images Vevey, a prestigious European photography prize that offers a R650 000 purse in support of producing new work.

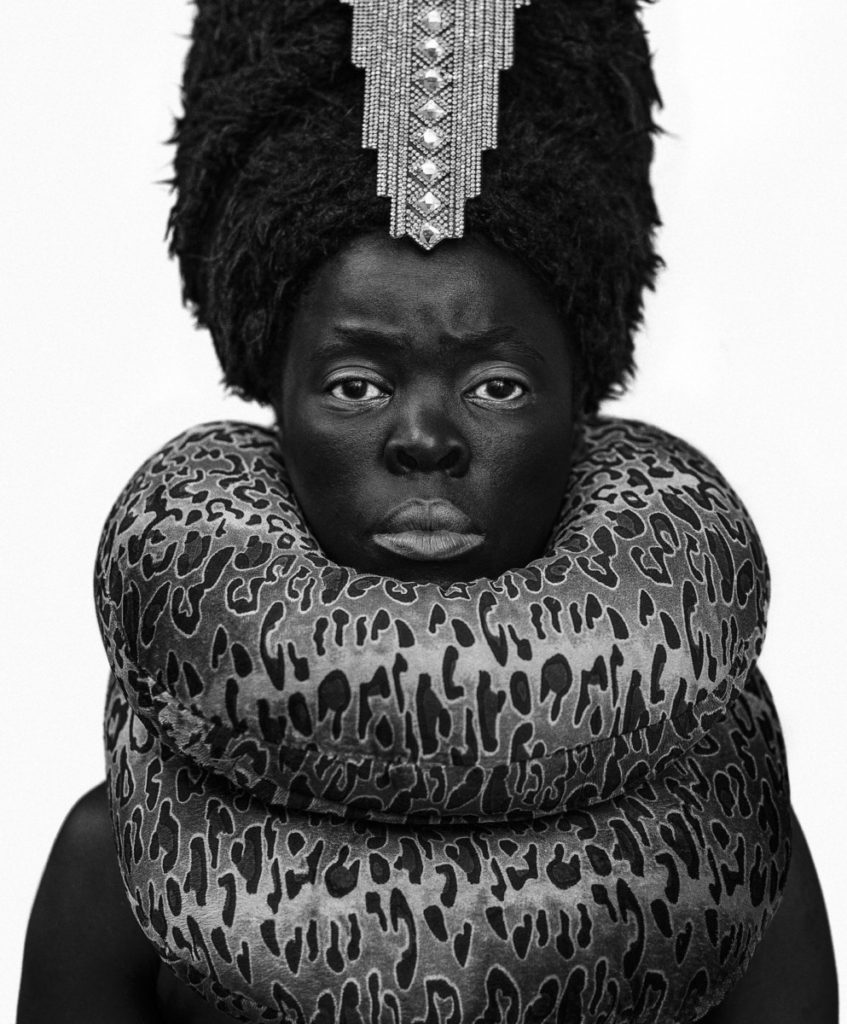

ZANELE MUHOLI, XINIWE AT CASSILHAUS, NORTH CAROLINA, 2016.

ARTWORK IMAGE COURTESY OF ARTIST, STEVENSON AND YANCEY RICHARDSON

The Images Vevey jury praised Kganye’s “intriguing and resonant” approach to photography, which is based on her reconstructions of archival photos from personal family albums. “Kganye has a practice deeply informed by the concerns and techniques of master artists from South Africa like William Kentridge, David Goldblatt, Sam Nhlengethwa, and Zanele Muholi,” remarked the jury, which was chaired by Nigerian-American writer and photographer Teju Cole and included Frederica Angelucci, a director of Stevenson Gallery.

Awards, especially at a young age, offer reliable smoke signals for collectors. Take, for example, the awards heaped on Pieter Hugo and Mikhael Subotzky at the start of their stellar careers. In the last few years, Kganye, a 31-year-old resident of Johannesburg currently completing her MFA at Wits University, has gathered a basketful of rosettes. In 2019 she received the Camera Austria Award for Contemporary Photography, and shared the spoils from last year’s Paulo Cunha e Silva Art Prize, a prestigious biannual Portuguese art prize judged by industry peers.

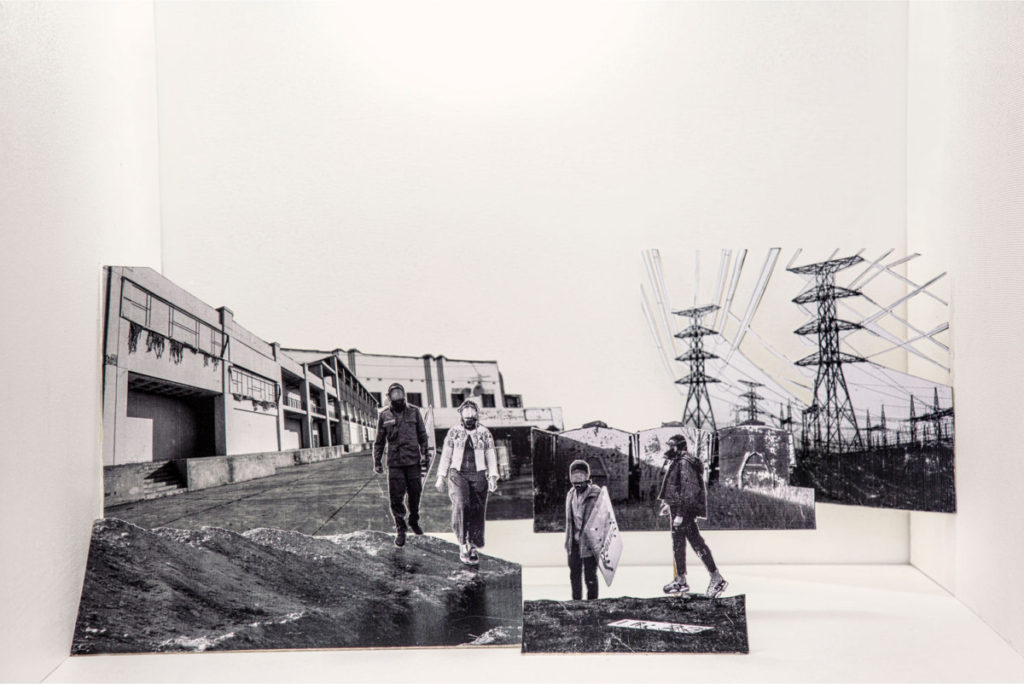

LEBOHANG KGANYE, THIS IS NOT WHAT I WANTED FOR ANY OF YOU, 2020.

ARTWORK IMAGE COURTESY OF ARTIST AND VEVEY, SWITZERLAND

The origins of Kganye’s imaginative practice, which draws photography into conversation with printmaking, sculpture, video and performance, can be traced back to her decision to study at the Market Photo Workshop in 2009. Originally intent on studying journalism at Wits University, when her application was rejected Kganye enrolled in a photojournalism course at the photography school founded by Goldblatt in 1989. Her awareness of photography was, she admits, negligible.

“I had read something about Kevin Carter and the Bang-Bang Club,” says Kganye in reference to a collective of male photographers who documented South Africa’s turbulent transition to democracy in the early 1990s. “It was never really my plan to be at the school longer than a year. It was just a way to pass time before I reapplied again for journalism at Wits.” Kganye ended up pursuing advanced level studies at the Market Photo Workshop until 2011.

In 2012, two years after her mother’s death, Kganye was awarded a Tierney Fellowship for a project about her ancestral roots. The mentorship award enabled Kganye to travel and meet with her scattered matrilineal family, as well as work with artist Mary Sibande and curator Nontobeko Ntombela as mentors. “I was always fascinated by more physical work,” says Kganye, whose photography and film practice slots into traditional performative photography that links her to artists like Tracey Rose and Berni Searle. “I’ve always felt that I connect more through touch. Asking Mary to become my mentor, it made sense.”

TRACEY ROSE, MAQEII FROM SERIES CIAO BELLA, 2020.

IMAGE COURTSEY OF ARTIST AND GOODMAN GALLERY, JOHANNESBURG

In August 2013, Kganye presented two highly original photographic projects as part of her exhibition “Ke Lefa Laka” (It’s my inheritance, in Sotho). Ke Lefa Laka: Heir-story (2013) presented Kganye wearing her grandfather’s oversized suit, re-enacting family stories in artificial cityscapes. Ke Lefa Laka: Her-story (2013) showed Kganye superimposed into old family snapshots depicting her mother, mimicking her poses as well as wearing her clothes. Influential German photography collector Artur Walther acquired a full edition of the latter series for his pacesetting collection.

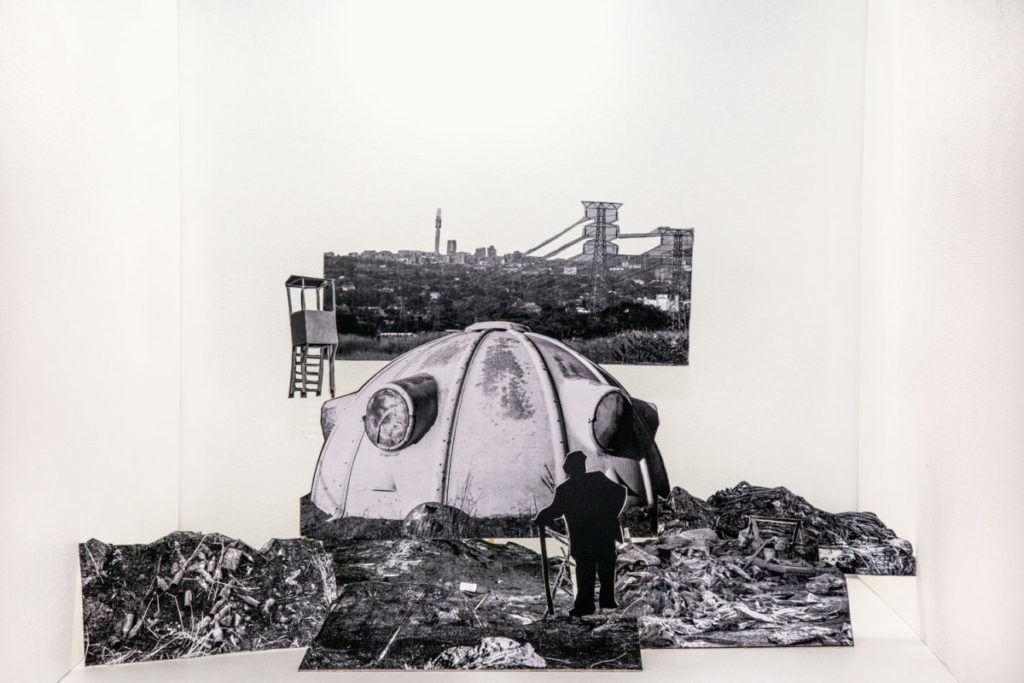

Kganye’s method of inhabiting and animating family photos remains the basis of her much-admired practice. Her proposal for Images Vevey is to create a large-scale theatrical installation using archival photos. The new work will additionally draw on her interest in children’s pop-up books, Malawian writer Muhti Nhlema as well as research Kganye did in 2018 into watchmaking and automatons during a residency in Geneva.

LEBOHANG KGANYE, THE STRANGER STOOD BEFORE A MONSTROSITY, 2020.

ARTWORK IMAGE COURTESY OF ARTIST AND VEVEY, SWITZERLAND

Kganye is represented by Afronova Gallery, where her photographs sell for €3,800-6,000 (R66,000-105,000), depending on the edition number. Founded in Johannesburg by Brussels-born French dealer Henri Vergon, Afronova helped establish the career of acclaimed textile artist Billie Zangewa. The gallery has actively promoted women photographers, early on showing Jodi Bieber, a decorated Johannesburg photographer known equally for her gritty assignment work and ennobling portraits of women.

Aside from Kganye, Afronova currently represents photographers Phumzile Khanyile and Alice Mann, who are each generating substantial smoke signals too. In July, Khanyile showed work at Rencontres d’Arles, a prominent French photo festival. Her solo exhibition “Plastic Crowns” featured mostly self-portraiture first seen in her Market Photo Workshop solo in 2017, and she also had work in Photo Slam!, a group show curated by Gagosian Gallery curator Antwaun Sargent. Mann, winner of the 2018 Taylor Wessing Prize and one of art market site Artsy’s most in-demand artists of 2020, will launch a photobook compiling her portraits of Cape Town drum majorettes at Paris Photo in November.

ALICE MANN, DERNIKA WILLIAMS, 2017.

ARTWORK IMAGE COURTESY OF ARTIST AND ARFONOVA GALLERY, JOHANNESBURG

ALICE MANN, TAYLIM PRINCE, 2017.

ARTWORK IMAGE COURTESY OF ARTIST AND ARFONOVA GALLERY, JOHANNESBURG

“We only want to work with originals,” says Emilie Demon, who now heads up Afronova following Vergon’s untimely death in 2020. Afronova long ago closed its Newtown gallery space to concentrate on art fairs and collaborations. The gallery recently collaborated with Johannesburg dealer Kimberley Cunningham, who hosts selling exhibitions in an artist-built house in Parktown North, to showcase work by Khanyile and Mann. Khanyile’s photos currently sell for €2,800-5,000 (R49,000-87,000), and Mann’s work is priced €3,000-7,000 (R52,500-122,500), depending on the edition number.

PHUMZILE KHANYILE, PLASTIC CROWNS, EDITION OF 8, 2016.

ARTWORK IMAGE COURTESY OF ARTIST AND ARFONOVA GALLERY, JOHANNESBURG

PHUMZILE KHANYILE, PLASTIC CROWNS, EDITION OF 8, 2016.

ARTWORK IMAGE COURTESY OF ARTIST AND ARFONOVA GALLERY, JOHANNESBURG

Other young dealerships fronted by women offering women photographers include THK Gallery, which operates spaces in Cape Town and Cologne. Founded by German photographer and collector Frank Schönau in 2018, who has since partnered with Linda Pyke, THK represents Manyatsa Monyamane and Nonzuzo Gxekwa. Both photographers were brought into the gallery’s fold over the past year and given solo shows. Gxekwa, who makes competent studio portraits, has had strong international sales in the price range €700-1,900 (R12,000-33,000). Manyatsa, a narrative portraitist currently completing her MFA at Wits University, sells in the range €1,500-1,800 (R26,000-33,000).

NONZUZO QXEKWA, UNTITLED 02, 2020.

IMAGE COURTESY OF ARTIST AND THK GALLERY, CAPE TOWN

NONZUZO QXEKWA, UNTITLED 04, 2020.

IMAGE COURTESY OF ARTIST AND THK GALLERY, CAPE TOWN

“While the international photography market is more established, we are finding a growing and receptive local audience,” says Linda Pyke, who like Kimberley Cunningham is a former Goodman Gallery staffer with work experience internationally. “There is an element of on-going education to establish the genre but there is definitely growing traction.”

Education is an important part of creating a collector market for photography in South Africa. To this end, auction house Aspire has partnered with veteran photographer Paul Weinberg’s Photography Legacy Project to create a regular African Photography Auction. Is this activism making a difference? Perhaps. After decades of antipathy, South African collectors are warming to photography, an oddball medium birthed by printmakers but sometimes priced like painting.

In 2019, for example, Athi-Patra Ruga’s eye-tingling 2013 portrait of a costumed figure astride a stuffed zebra, The Night of the Long Knives I, sold for R1.7 million at a Strauss & Co auction. Pieter Hugo routinely has work on the secondary market, with prices going as high as R900,000 internationally, and R500,000 locally – this after three Hugo portraits sold for R2,000 each at a Cape Town auction in 2006.

ATH-PATRA RUGA, THE NIGHT OF THE LONG KNIVES, 2013.

IMAGE COURTESY OF ARTIST, WHATIFTHEWORLD GALLERY/STRAUSS & CO, CAPE TOWN.

Neither Muholi nor Ractliffe’s auction prices come near this. In April, Babaza I, Philadelphia, a 2019, self-portrait from the acclaimed series Somnyama Ngonyama, fetched £23,940 (R491, 978) at a Sotheby’s auction in London. Ractliffe’s prices lag far behind her deserved reputation. The imbalances that marred the appreciation of South Africa photography still persist.

Sean O’Toole is a journalist and editor based in Cape Town. He is a contributing editor to Frieze magazine