Written by Sean O’Toole

Every so often, give or take a decade, a generally disinterested South African public is jolted by news of the feverish rapture artist JH Pierneef inspires in collectors. The news typically involves exorbitant sums of money paid by an obscure class of mandarins – corporate titans, wealthy expats and Ace Magashule’s former bodyguard – with a yen for modernist landscape paintings portraying billowing clouds looming over open ranges populated by indigenous trees, notably the camel thorns and baobabs typical of South Africa’s northern interior.

It happened again recently, amidst a cataclysmic pandemic and global economic slump. In July, auction house Strauss & Co successfully sold all 69 lots offered in a boutique auction exclusively devoted to Pierneef, a Pretoria-born painter whose precise graphic style and sumptuous treatment of landscape rendered the dominant modes of naturalism and impressionism of post-union South Africa moribund. The sale, which featured an encyclopaedic offering of works made between 1901 and 1955, earned a total of R24.58-million, surpassing the pre-sale estimate.

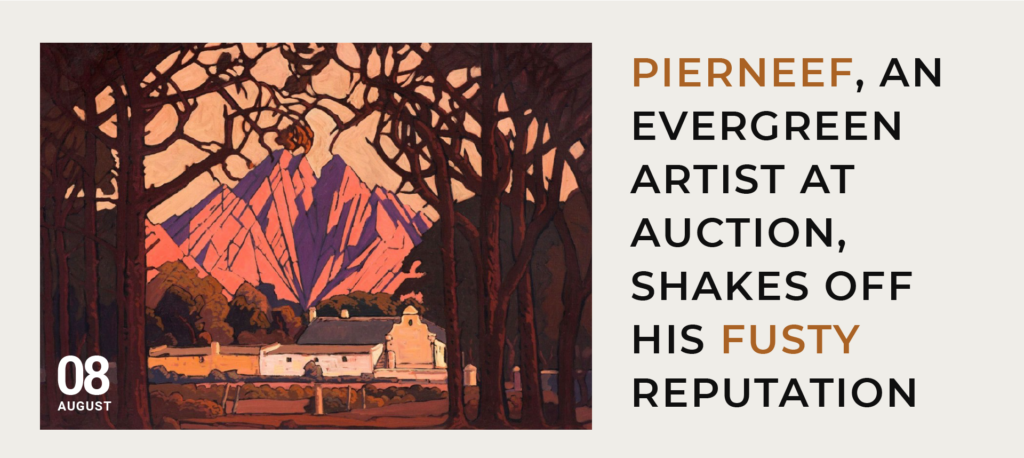

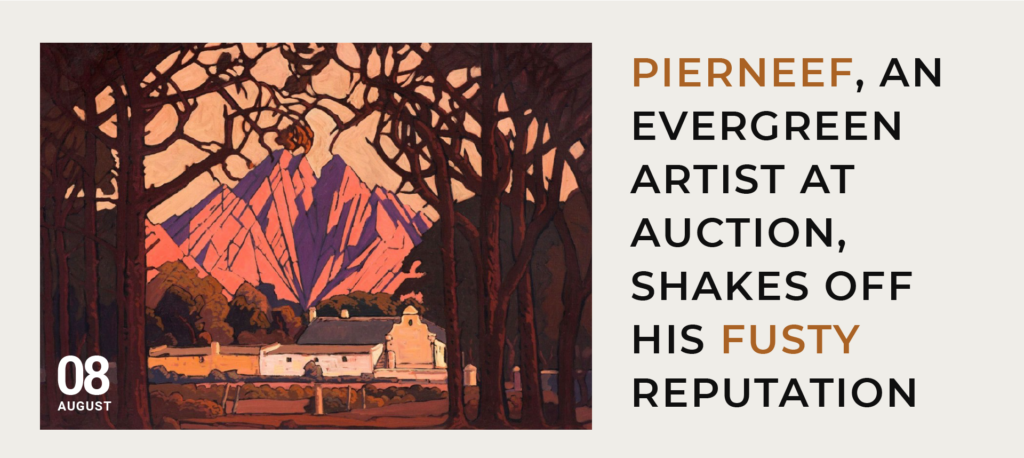

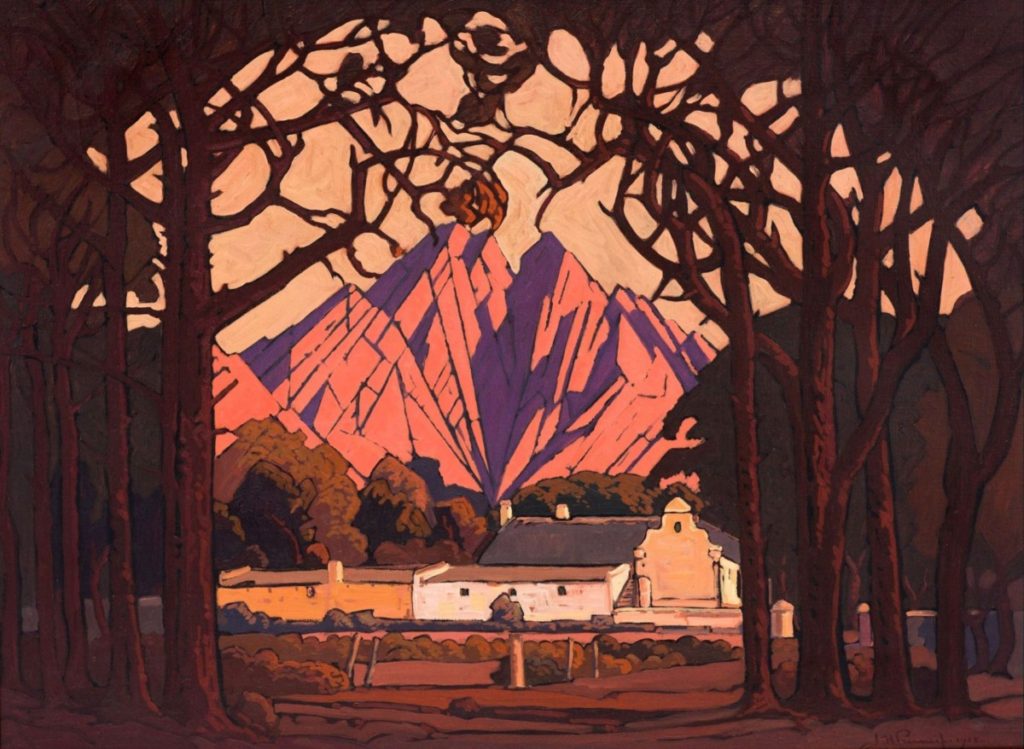

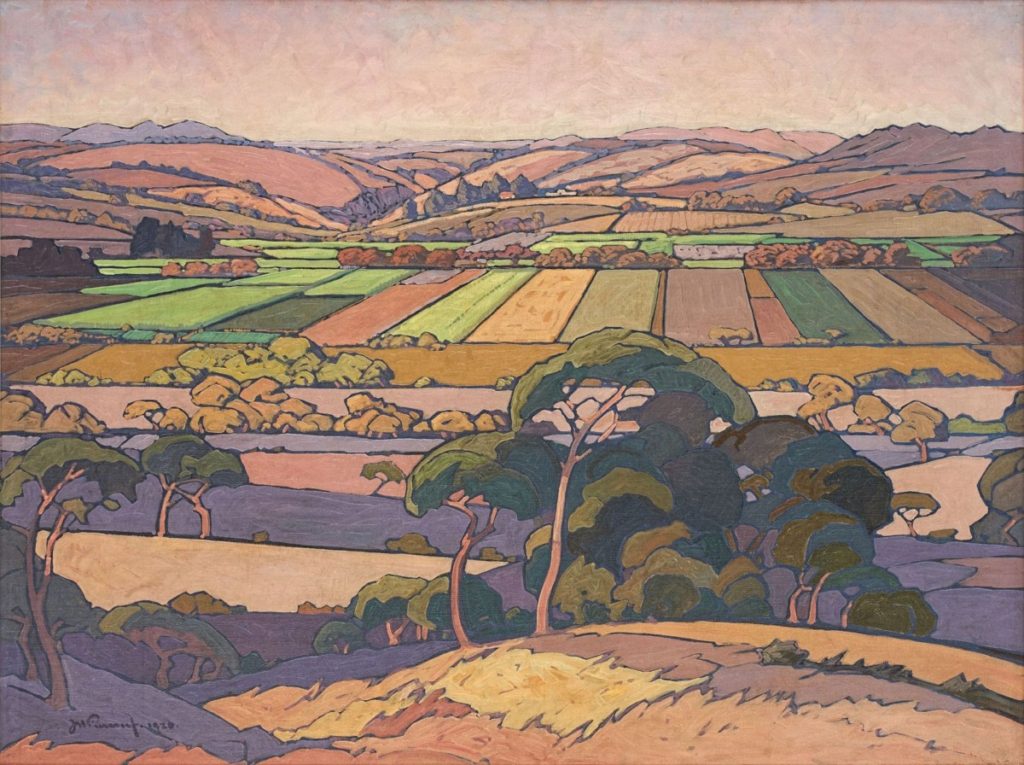

JH Pierneef, Farm Jonkershoek with Twin Peaks Beyond, Stellenbosch, 1928, oil on canvas.

Image courtesy of Strauss & Co.

The result may not match the February sale at Sotheby’s New York of all 373 lots from the New York apartment artist husband-and-wife duo, Christo and Jean-Claude, but it nonetheless earned the Strauss sale – billed as “In/Sight: JH Pierneef” – the rare auction accolade of being a white-glove sale, industry parlance for a flawless sale.

“In/Sight: JH Pierneef” opened with Man Digging (1901), an atypical early work produced in exile in the Netherlands during the South African War (1899-1902), which sold for R125 180. The ensuing lots included drawings, linocuts, watercolours, a rare casein, an even rarer etching and, of course, highly collectable oils. The pick of the oils was a winter bushveld scene, Acacia in the Veld (1940), which sold for R2.6million. The only other oil to breach the R2-million mark was Clouds over the Karoo (1953), an extensive landscape with lead-coloured storm clouds, which sold for R2.5 million.

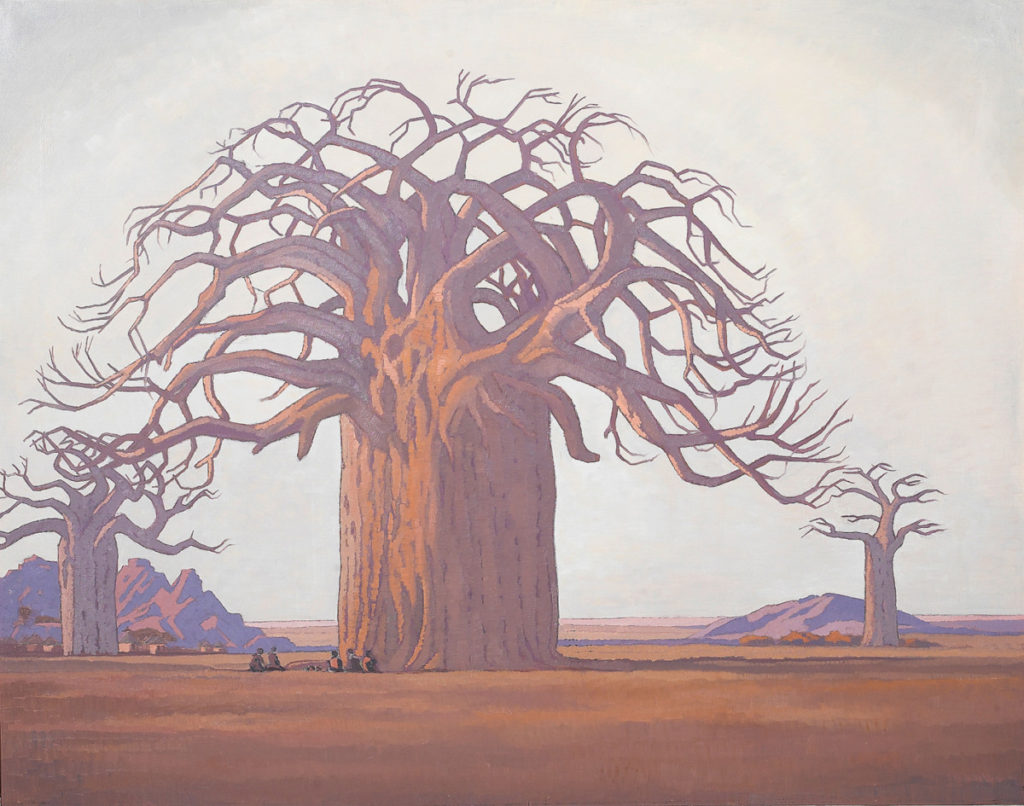

Given the impressive prices achieved by Pierneef oils in the past – R20.46 million for Farm Jonkershoek with Twin Peaks Beyond, Stellenbosch (1928) in 2017 at Strauss & Co, and R11.72 million (£826,400) for The Baobab Tree (1934) in 2008 at Bonhams, London – the July results were relatively humdrum. But the real story of the Strauss sale is in the prices achieved for Pierneef’s linocuts and reference books published in the decades after the artist’s death in 1957. They were nothing short of extraordinary.

JH Pierneef, The Baobab Tree, 1934, oil on canvas, 112 x 142,5cm.

Image courtesy of Bonhams, London.

The sale established a new world record for a Pierneef linocut when a 1941 print depicting an imperious baobab tree sold for R432 440. Pierneef’s linocuts were an important source of the artist’s popular appeal during his lifetime, appearing on magazine covers, notably Die Nuwe Brandwag (1929-33), and books of verse by poet Totius (aka Jacob du Toit).

Pierneef’s linocuts have also long functioned as an entry-level collectable for neophytes. This point of access may now be closed. There has been a noticeable run on Pierneef’s linocuts in recent years. The recent Strauss sale amply confirmed this trend. Other linocuts that went above estimate included Kruiskerk, Tulbagh (1933), sold for R170 700, and Twee Jonggezellen, Tulbagh (1933), sold for R153 630.

The steady appreciation in value of Pierneef’s linocuts is grounded in rational laws of supply and demand linked to solid prestige. The huge prices achieved for Pierneef reference books are, however, less easy to explain. An Afrikaans edition of editor PG Nel’s 1990 book of essays, JH Pierneef: Sy Lewe en Sy Werk, sold for the remarkable sum of R43 244. A numbered edition of author and journalist JFW Grosskopf’s 1945 monograph Pierneef: Die Man en Sy Werk, signed by both artist and author, fetched R10 553. Auction website BidorBuy is offering these books at considerably lower prices.

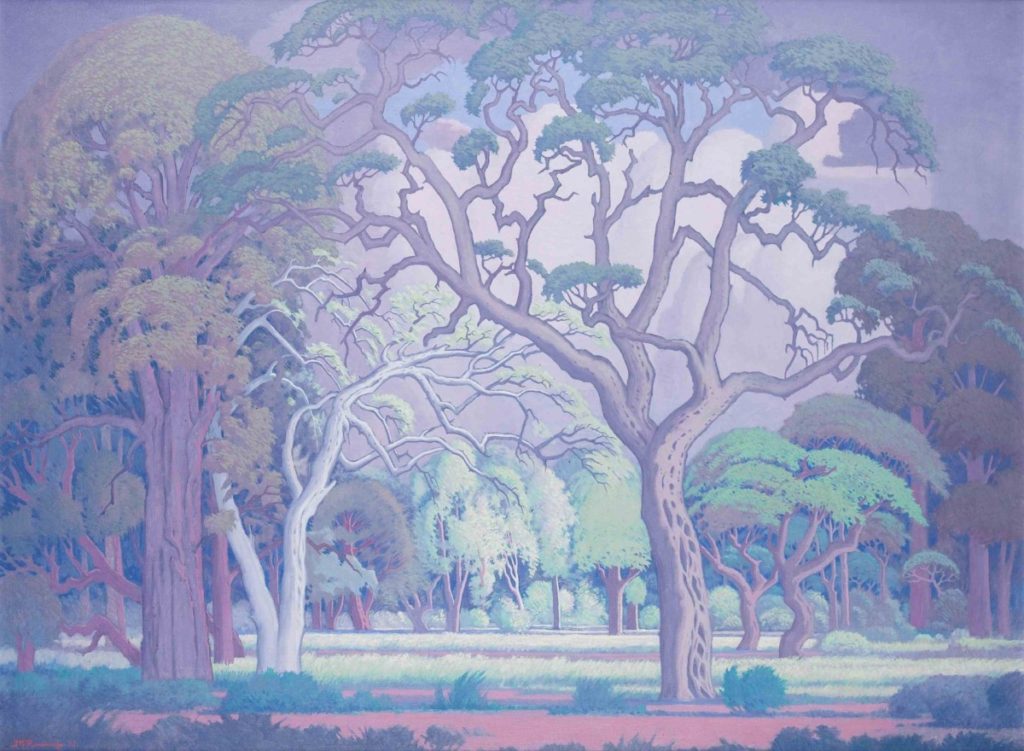

JH Pierneef, Bosveld, 1953, oil on canvas, 75 x 100cm Courtesy Strauss & Co, Johannesburg.

Courtesy of Strauss & Co.

Arguably the biggest surprise among the books was the hefty price of R21 105 paid for art historian NJ Coetzee’s 1992 book Pierneef, Land and Landscape: The Johannesburg Station Panels in Context. “Pierneef s landscapes are clearly an outsider’s view of the land, a view of the land that was de-historicized, de-humanized, drained of compassion,” wrote Coetzee. “It is a view that is at the same time informed by a sterile religious mysticism.” Coetzee’s book is still regarded as controversial by those who regard Pierneef’s unsullied landscapes as unimpeachable, but in many ways Coetzee’s writings merely summarised a chorus of anti-Pierneef criticism.

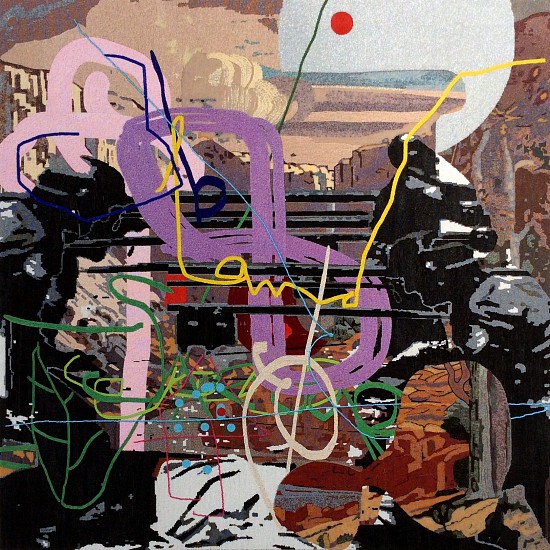

Unusually perhaps, the criticism was led not by the academy but by artists, among them Wayne Barker, William Kentridge and Andre van Zijl. In his insightful 1988 essay “Landscape in a State of Siege”, Kentridge described Pierneef’s highly orchestrated scenes of “pure nature” depicting kloofs, escarpments and trees as “documents of disremembering”. In 1989, Barker destroyed a facsimile of Pierneef’s Apies River composition, part of the 32 panels for his career-defining Johannesburg Railway Station commission (1929-32), in a workingmen’s bar in central Johannesburg during the filming of a television documentary on artist Braam Kruger.

Wayne Barker, Strange Fruit, mixed media.

Image courtesy of Everard Read Cape Town.

These brickbats are explained by an earlier wave of adulation – at market, but also by the apartheid state – that built a cult around Pierneef. Generously lavished with praise and patronage in his later years, Pierneef’s death in Pretoria in 1957, at age 71, heralded the start of a magical second act. In 1971, auction house Sotheby’s sold Pierneef’s oil Laeveld (1945) for R8 800 (£4 400) at its maiden Johannesburg sale. It was a highlight for the new auction house operated by dealer Reinhold Cassirer, the husband of novelist Nadine Gordimer and Kentridge’s first agent.

A decade later, in 1981, Marino Chiavelli, an Italian businessman and sanctions buster resident in Johannesburg, established a new auction record for Pierneef when he paid R33 000 for Summer Clouds in the Bushveld at a Sotheby’s auction in Johannesburg. In 1985, Pierneef became the first South African artist to breach the magical R100 000 mark when his composition, Extensive Landscape Northern Transvaal, sold for R120 000.

JH Pierneef, Extensive Landscape Northern Transvaal, 1949, oil on canvas.

image courtesy of Strauss & Co.

Collectors of Pierneef weren’t exclusively drawn from the private sector. In 1980, the Department of National Education – acting on a longstanding tradition of patronising the artist – paid Pierneef’s daughter, Marita Bailey, R1 million for 330 paintings, drawings and graphic work by the artist. Parks and suburbs were also named after the artist.

The critical backlash against Pierneef in the later 1980s and early 1990s suggested a dim future for him in the reconstruction years after 1994. The art market proved otherwise. In 1995, a cubistically patterned landscape dominated by a camel thorn from 1925 sold for R209 000. In 2003, amidst a general slump in prices for South African art, Pierneef bucked the prevailing trend when his composition Krokodilpoort by Nelspruit sold at Stephan Welz & Co/ Sotheby’s for double the price paid it had achieved in 1994. And so the story generally continues.

Appetite for “showstopper” and “mega-trophy” Pierneefs of the order of Farm Jonkershoek and The Baobab Tree persists. “Right now there’s someone sitting in London, someone in Pretoria, and a half dozen other collectors, none of whom really want to water down their savings and buy five smaller Pierneefs – they want a beast,” confirmed a Strauss representative. It is not just auction houses that are responding to this unbridled appetite for Pierneef.

Following a wave of hip Pierneef bashing that culminated in artists Zander Blom, Jan Henri-Booyens and Michael MacGarry dancing on Pierneef’s grave in 2007, artists have increasingly looked to Pierneef for ideas and inspiration. In 2010, sculptor Wim Botha created Blastwave, four tree sculptures installed in the atrium of Nedbank’s Sandton headquarters. Their bent yet resistant form acknowledges a possible afterlife for Pierneef’s once untroubled trees.

AVANT CAR GUARD at J.H. Pierneef’s Grave, 1954, 2006

Image courtesy of Artsy.net

More so than his clouds and mountains, Pierneef’s trees have fired the imagination of a new wave of contemporary artists. Last year, in a presentation at SMAC in Cape Town, Marlene Steyn irreverently quoted Pierneef’s acacias, baobabs and willows in a series of winsome pastel-hued acrylics. An earlier composition in this style, I am Bush Myself (2019), sold at the 2019 Cape Town Art Fair for R145 000. Fellow SMAC painter Kate Gottgens is currently at work on a large canvas work inspired by

Pierneef’s early-career willows, which distilled his naturalist subject matter and heralded his abilities as a colourist.

Marlene Steyn_I am bush myselves_2019_Oil, Goldleaf & Mixed Media on Canvas. 170 x 170 cm.

Image courtesy of SMAC Gallery.

Around the corner for SMAC is 131A Gallery, a new dealership that represents two Cape artists linked to Pierneef. Michael Amery is an accomplished graphic artist with an interest in trees as compositional subject as well as signifier of environmental peril – invasive vegetation poses a greater threat to our water supply than climate change. For his recent June solo exhibition at 131A Gallery, Amery leaned heavily into Pierneef’s picturesque technique and cubistic arrangement of space. His approach clearly appealed. Most of Amery’s acrylic paintings, charcoal drawings and laser-cut brass sculptures (priced between R12 000 and R48 000) found buyers.

Michael Amery, Geometrics 34, 2021, acrylic on stretched canvas.

Image courtesy of 131A Gallery.

MJ Lourens, Outskirts 1, Gauteng 2021, acrylic on board.

Image courtesy of 131A Gallery.

Like Pierneef, Lourens is a fabulist. He draws on art historical devices and tropes in his portrayal of fictionalised urban and industrial settings, framed by trees and billboards and topped by billowing (and also bitmapping) clouds. In 2019, 14 of his large acrylic paintings (priced R65 000 and up) were shown alongside works by Pierneef at La Motte, a wine estate in Franschhoek owned by a scion of the Rupert family, well-known collectors of Pierneef and guardians of his legacy.

“Shown in tandem with the landscapes of an earlier age represented by Pierneef,” wrote curator Hayden Proud in catalogue for the exhibition, titled “Land Rewoven”, Lourens’ works reveal that “they are no mere revival of earlier concepts of ‘the sublime’, but use the experience of that same impulse to address the ecological emergencies of our moment”.

After decades of ambiguity, Pierneef appears to be losing his fusty reputation. Amidst our current storm of economic, ecological and ideological crises, he has proven to be a bit like his acacias: a resilient evergreen, one that every so often, as the season dictates, produces a radiance of puffball bloom clusters whose meaning needs understanding.

Sean O’Toole is a journalist and editor based in Cape Town. He is a contributing editor to Frieze magazine