Written by Sean O’Toole

There’s a long history of South African artists coming together, either of their own volition or through the intervention of an art dealer, and making a big splash together. The Stellenbosch Four – aka artists Katharien de Villiers (b. 1991), Jeanne Gaigher (b. 1990), Amber Moir (b. 1990) and Marlene Steyn (b. 1989) – are not a new addition to this history of collective doing. This is because there is no clique, club or collective to speak of.

Each of these four artists has cultivated a rigorous individual practice. And yet, this quartet of loosely affiliated painters in their early thirties – all of whom graduated from Stellenbosch University between 2011-14, and all of whom have gone on to work with painting in an expanded field of possibility – have about them an air of camaraderie that recalls the Wits Group. It helps to know that the Wits Group never existed either, not in any formal sense.

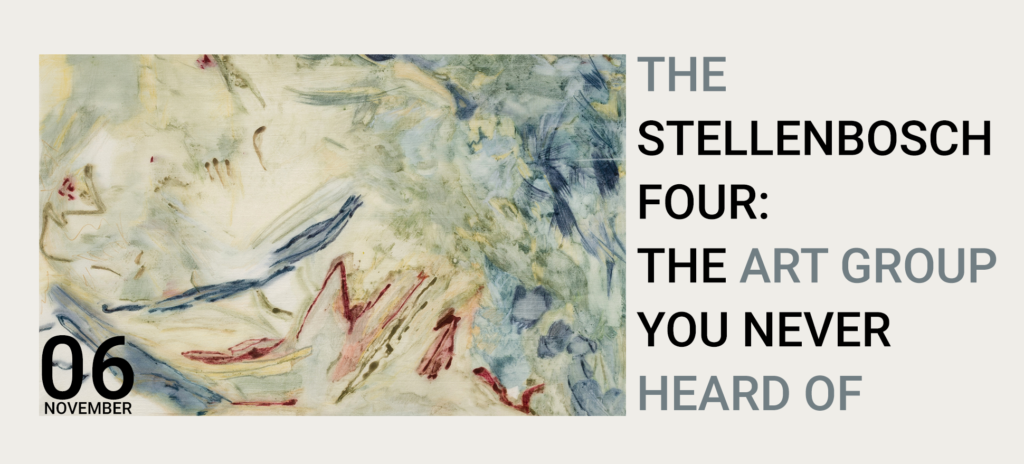

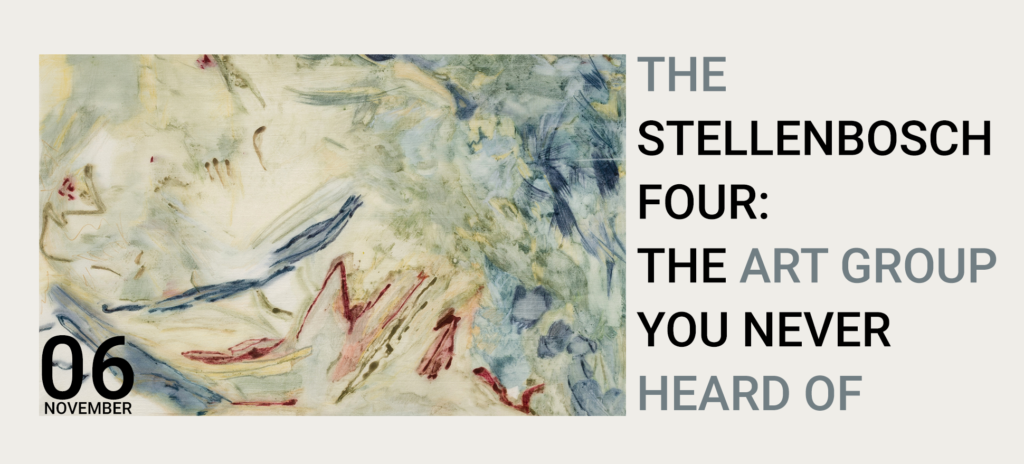

Jeanne Gaigher, Crackling noise, 2021, acrylic, ink on canvas and scrim, 181 x 337cm.

Courtesy of the artist and Osart Gallery, Milan.

Art critic Esmé Berman invented the name in 1961 to account for the “intimate atmosphere” and “fellowship” among a group of artists – Christo Coetzee, Nel Erasmus, Larry Scully, Cecil Skotnes and Gordon Vorster – who studied at the University of the Witwatersrand between 1946-50. “Choice and chance continued to bring various members of the group into professional associations after graduation,” wrote Berman in 1970, adding that the “disparity between their styles” made it illogical to think of them as a coherent group.

The same broadly holds true of the Stellenbosch Four. While connected by a quirk of biography, having all studied together at Stellenbosch University at roughly the same time, their individual practices nonetheless greatly differ.

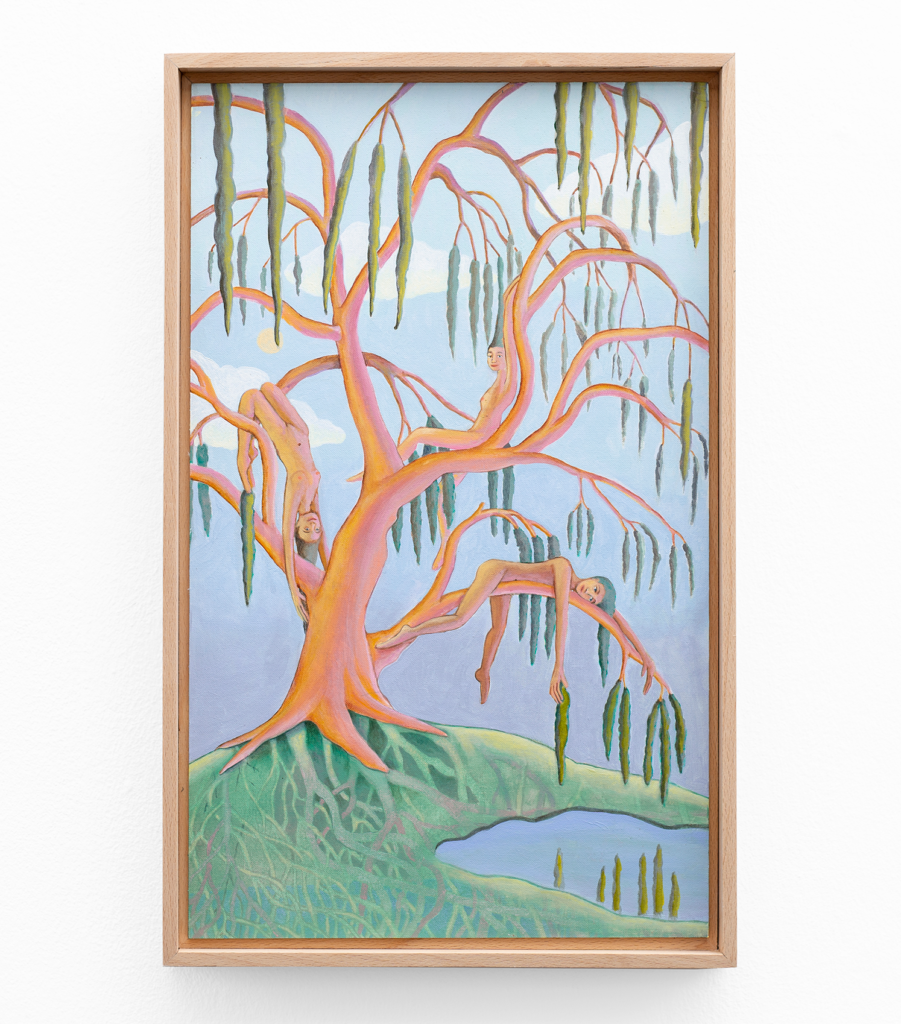

Steyn, the oldest in the group, is an insistently figurative painter whose work is fed by radical theory and psychology. Her trippy compositions featuring tangled figures and multiplied selves in floral paradises and aquatic kingdoms are both whimsical and defiant. “I’m very interested in the process we follow to create a sense of self in this contemporary time – especially as a female,” Steyn told artnet News in 2018. “My work is a combination of deep-diving into the conscious, trying to find calm in the craziness of everyday life, while spiritually trying to make sense of what a self is.”

Marlene Steyn, Stroke my palms and flush my knee, 2016, oil on Canvas, 170 x 170cm.

Courtesy of the artist and SMAC Gallery, Cape Town.

Moir is an experimental printmaker whose abstract monotypes are informed by chance outcomes. Process and risk are central to her ambitiously scaled and frequently unframed pitch-rolled watercolour monotypes, which additionally feature delicate gestural marks redolent of abstract expressionism. “I have increasingly diverged from the printmaking idea that once a print is printed it’s finished,” Moir told me earlier this year. “I really struggled with that rule at university. I’ve become a lot more comfortable with the idea of these printed textiles or pieces of fabric as being raw materials that I can work with and explore what they mean – and what they can be.”

Gaigher’s layered and materialist approach to figurative painting purposefully confuses traditional binaries between material and icon, as well as figure and ground. Her intricately worked surfaces and irregular edges are as integral to the meaning of her work as the prostrate and huddled female figures at their centre. “I am particularly interested in the anatomy of the canvas itself – the construction of the substrate that the image is painted on,” Gaigher has said of her new work. “I use the word ‘anatomy’ in relation to the surface, which is built up with layers of curved canvas shapes, stitched together, mimicking the silhouettes of organs and limbs.”

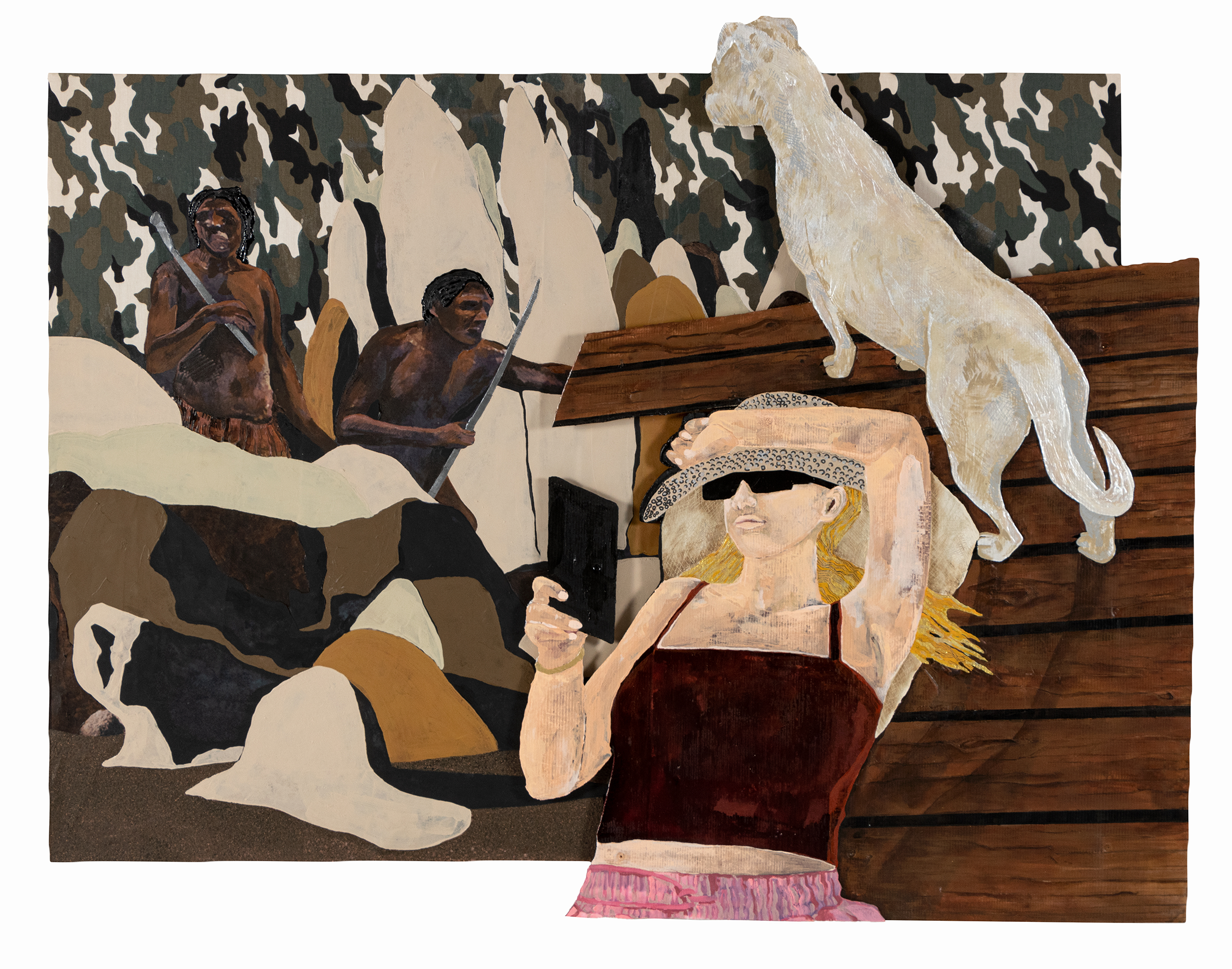

De Villiers’s recombinant approach to image making has a strong basis in sculpture. Like Steyn, she furthered her studies abroad, completing a MFA in installation at Royal Academy of Fine Arts (KASK) in Gent, Belgium. Of the four, her work is the most responsive to vernacular culture and found materials, lending her compositions a vibrant pop sensibility. Her compositions frequently spill out of their frames. “Rigid boundaries can only appeal to believers in truth,” writes De Villiers in a ‘zine she produced during a residency at A4 Arts Foundation earlier in 2021. “But on a formal level, breaching the frame also highlights the ‘construction’ of images.”

Amber Moir, All acts of spring, 2021. watercolour monotype, collage on calico. 1200 x 1980mm. Unframed.

Courtesy the artist and Salon 91, Cape Town.

As ought to be clear, the four artists work in very different ways. Conspicuously, Steyn is the only artist with a track record in the secondary market. Last month, auction house Strauss & Co sold Steyn’s 2017 composition The Leaf Blows Hers for R136 560. Her retail prices also far outstrip her friends.

And yet, for all that distinguishes their approaches to form, line, colour, surface and edge, as well as the vagaries of success at market, “choice and chance” has repeatedly brought these four artists into conversation. The career intersections are many and, when given due consideration, hint at something more than just coincidence.

Katharien De Villiers, Enroute Through the Anthropocene, 129 x 102 x 6cm.

Courtesy of the artist and Osart Gallery, Milan.

Starting in 2015, a time of agitation and change in South African culture, De Villiers and Gaigher began showing at Candace Marshall-Smith’s now-defunct space Smith Studio. Buoyed by an interested market, they presented increasingly assured solo exhibitions featuring noticeably haptic propositions of what painting can be, not should be.

This year, De Villiers and Gaigher have again shown with the same gallery, each presenting confident solo exhibitions with Osart Gallery in Milan. This association with dealer Andrea Sirio Ortolani goes back to 2019, when Gaigher and Steyn first exhibited at Osart in a three-person show with Zimbabwean artist Kresiah Mukwazhi.

Marlene Steyn, Muted Fishwife, 2019, polyurethane resin, 163 x 150 x 200cm.

Courtesy of SMAC Gallery, Cape Town.

Closer to home, De Villiers and Steyn last year exhibited together in Shaping Things, an engaging showcase of new works in clay and ceramic by 31 artists and collectives organised by SMAC Gallery in Stellenbosch. Steyn especially is noted for her ceramic production.

“For me, working clay is a haptic and more immediate approach to thinking about the precarious and ever changing states of subjectivity, which stands in stark contrast to my paintings that are tighter and often take months to complete,” said Steyn in 2017 when her ceramic work was profiled in art publisher Phaidon’s international survey book Vitamin C: Clay and Ceramic in Contemporary Art.

Although represented by Monique du Preez of Salon 91, Moir has also shown work at Baylon Sandri’s SMAC. In 2018 she presented three of her enigmatic monotypes in SMAC’s printmaking show Proof. The artist line-up included Larry Scully, a grand poobah of abstract painting who headed up Stellenbosch University’s fine art department between 1976-84. Scully’s experiments with staining from the 1960s are one of many historical reference points clarifying the lineage of Moir’s gorgeous work.

Formal art making aside, the Stellenbosch Four have also dabbled in other areas of creative practice, notably fashion. In 2018, Gaigher, Moir and Steyn produced one-off luxury silk scarves for a project spearheaded by the Norval Foundation. That same year, Steyn collaborated with Lisa Jaffe of fashion brand Guillotine on a ready-to-wear range imprinted with an eye-tingling tangle of figures. Over the course of 2021, Gaigher has been collaborating with fashion designer Lukhanyo Mdingi on a knit dress for commercial release. Its ribbed design quotes a recurring motif in Gaigher’s recent paintings.

Jeanne Gaigher, Lavender II, 2020, acrylic, ink on canvas and scrim, 208 x 190cm.

Courtesy of the artist and Osart Gallery, Milan.

Choice and chance is admittedly a wobbly peg on which to hang a story about a loose grouping of artists whose practices are heading in different directions. If anything, the story of iQhiya, the all-women artist group founded in 2015 by a cohort of art students from the Michaelis School of Fine Art – among them Bronwyn Katz, Bonolo Kavula and Lungiswa Gqunta – speaks more directly to the meaning of collective practice in our post-white, fem-interested art present. But Michaelis, like Wits, has a way of hogging the limelight. What about Stellenbosch?

“History, as people I spoke with for this article constantly reminded me, complicates things. Over the course of the last century, Stellenbosch University emerged as an intellectual redoubt for a virulent brand of white Afrikaaner nationalism. In 1936, for example, a group of Stellenbosch professors, including H.F. Verwoerd, gathered in Cape Town to protest the impending arrival of a ship carrying German-Jewish immigrants – among them artist Hanns Ludwig Katz. One person I spoke with, a fellow art student and close friend of the Stellenbosch Four, said the university’s history “presides over everyone” and “makes you feel embarrassed”.

Amber Moir, Wind and Silver I, 2020., watercolour monotype on calico. 2035 x 1055mm. Framed.

Courtesy the artist and Salon 91, Cape Town.

This history is squarely confronted in a new book, Troubling Images: Visual Culture and the Politics of Afrikaner Nationalism, which looks at the role visual culture in rationalising and normalising white settler culture. The book is co-edited by Lize van Robbroeck, an associate professor at Stellenbosch University’s Visual Arts Department and Vice Dean of Arts. Van Robbroeck is a dynamic thinker and doer. Along with Kathryn Smith and others, she has renovated the conservative, academic-style art school established at Stellenbosch University in 1963 under the leadership of the German expatriate artist Otto Schröder.

Outsiders are increasingly taking note.

Marlene Steyn, we will…oh willow!, 2020, acrylic on canvas board, 50 x 30cm.

Courtesy of the artist and SMAC Gallery, Cape Town.

“The art school holds such a different set of frequencies to that of Michaelis,” says artist James Webb, an admirer of Moir and other students mentored by Smith. “Well, that’s my projection anyway, and I am thinking of artists like Anya de Klerk and Larita Engelbrecht whose work has always been their own lovely soft velvet weird, and not necessarily what the Art World™ is priming for.”

Jacob van Schalkwyk, an artist and novelist who lectures at Stellenbosch, credits the art school’s “strong foundation in technique” and “studio-heavy course” as important virtues. The university’s maligned and provincial status, he adds, also allows graduates to incubate and iterate their work in relative obscurity, this compared to Michaelis where the art market is more active and involved.

Katharien De Villiers in the studio, 2021.

Courtesy the artist and Osart Gallery, photo Paris Brummer

Shona van der Merwe, who studied with Moir and now operates as a curator and consultant, also credits the relative lack of a painting tradition within the art school – “painting was discouraged” – as a possible explanation for the experimental attitude to what painting can be among Stellenbosch graduates. What I mistook for shyness and a desire not to claim attention among some of the Stellenbosch Four, Van der Merwe also more correctly characterises as “groundedness” and “humility”.

What does it mean to be a young white painter in South Africa today, to be ambitious, capable, interested, engaged, but also somehow cast adrift by historical circumstance and the appetites of a changeable art market? It is a grandiose question, urgent yes, but overblown too. Obscurity dogs all young artists, whatever their race, gender or qualifications. If anything, the Stellenbosch Four affirm an unyielding cliché. You make, and you continue making. Eventually, curious eyes will see you.

Sean O’Toole is a journalist and editor based in Cape Town. He is a contributing editor to Frieze magazine