By Cur8.art

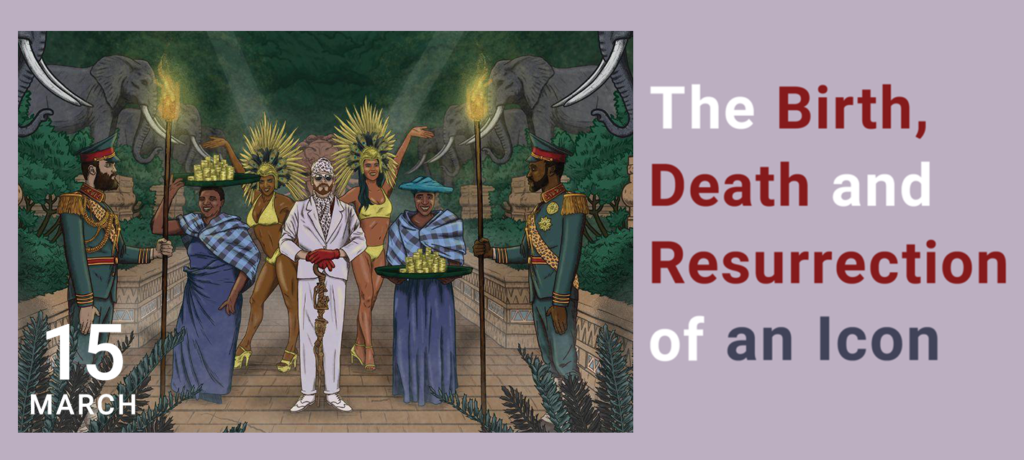

We recently met up with Xander Ferreira to chat about his intriguing career and what he’s been getting up to as an artist abroad. Most widely known by his moniker Gazelle, Ferreira wears many hats merging music, visual art and performance to forge theatrical episodes aimed at understanding the cyclical patterns of history. “By creating a fictional ‘His Story’ through his satirical character Gazelle, a playful commentary on cultural propaganda comes to life while he looks at how narratives of generational storytelling can become self-proclaimed truths.”

Take us back to your beginnings as an artist…

I didn’t grow up with art, I grew up on a very rural farm in Limpopo where we didn’t have art at school beyond the age of ten. The only experience was one’s own expressions with whatever materials you might find on the farm or in nature. My practice really started when I got a scholarship to go to the Open Window Art Academy in Pretoria through a competition that I entered and won, found on the pages of the Rooi Rose magazine. During my study of art history and visual communication, my practice began. During that time I saw the opportunities to go into the more lucrative side of creativity with advertising and decided to move to Cape Town and find a job.

Photography became my first medium or vocation when by chance I met a great mentor, the renowned Swiss photographer Marco Grob. Since then he has become one of the most respected portrait photographers in the world. He taught me everything I know about light, subject, and capturing a moment technically. It was my early twenties and I got super lucky through lots of hard work and was published by Hasselblad Victor Magazine as one of the seven up-and-coming young photographers in the world. My photography career exploded, but I wasn’t ready for the industry or experienced enough in life to truly play the part. I didn’t understand that in the business of advertising, you’re not purely an artist, you’re an engineer that crafts other people’s visions through your garnered skills.

So, I got very frustrated after a while and felt I needed a shift. A quintessential moment was when I was with a friend in Berlin, the painter Mustafa Maluka. While visiting his studio it was the first time that I had the opportunity to see an artist in practice, painting, creating and making a living from his work. This inspired me so much to see that it might be possible to spend one’s life making art. So I decided to give up everything and figure out what it meant to me, ‘ To make art’.

What is your definition of art?

I recall someone sharing that the act of creating art is simply that, “You choose a subject and you study it”. These simple words were so inspiring. So to me, art is no different from any exploration of a vocation or interest. Just as a biologist that decides to study flowers can become a botanist and specialise in the study of Proteas and so share the magical wonder of this plant to the world. So an artist can choose a subject and go down the rabbit hole to share the wonderment of beauty that they find with the world. You keep digging into that subject and the mediums eventually come out.

In the process of trying to figure out what it meant to create art I had to go back and look at my study of art history. I was fortunate to have wonderful teachers like the renowned South African artist Maja Marx who shared knowledge that stuck with me. I recalled after learning about all these art movements through the ages, we went on the mission to start our own movement with her husband Gerhard Marx and a bunch of other students. It felt like this was the energy I had to tap back into. Surrendering into exploration, action, and just letting go. So we ended up creating this group exhibition which was the first time I ever put art on a wall, it was at a panel beaters in Pretoria.

Your work is an amalgamation of visual art, performance and music, pushing boundaries and finding new ways to spark conversation on socio-political issues – how did this come about in your practice and what led you to the birth of Gazelle?

I became fascinated with iconography and how it can be used for power. Through my work in advertising I was mesmerised by how we were able to create visuals to sell shit to people that they didn’t need, all through using the power of beauty. So I became fascinated with how the underlying mechanics of branding works, especially within religion and politics. So, I thought, let me delve down this rabbit hole.

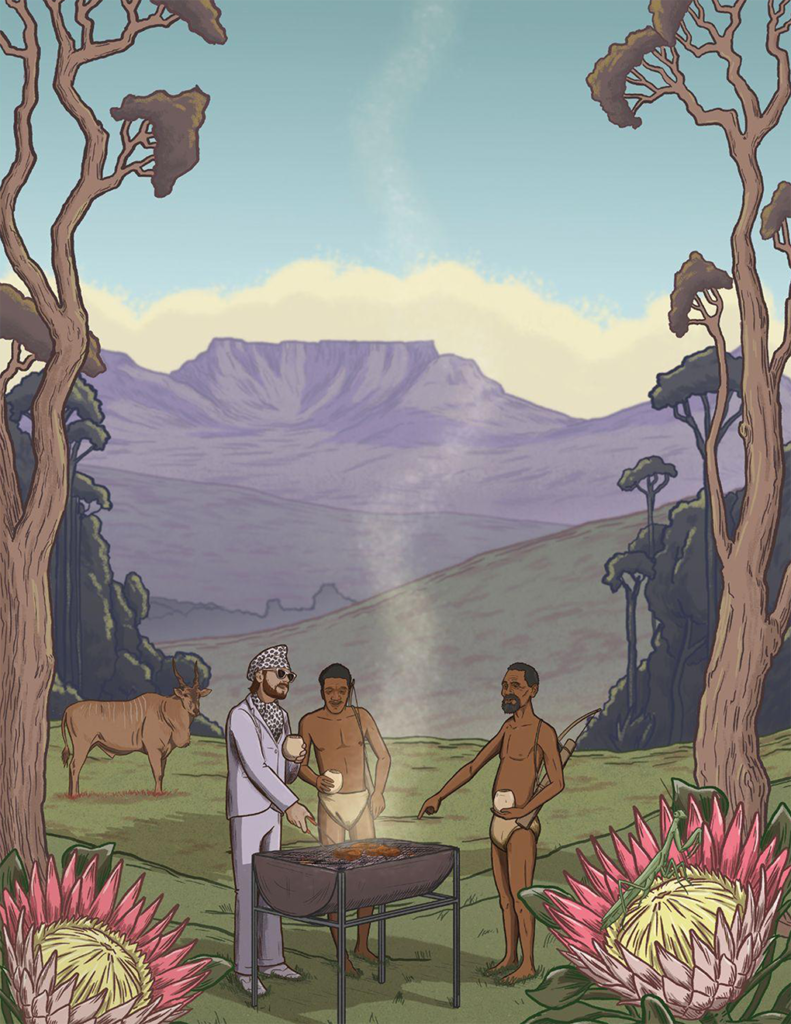

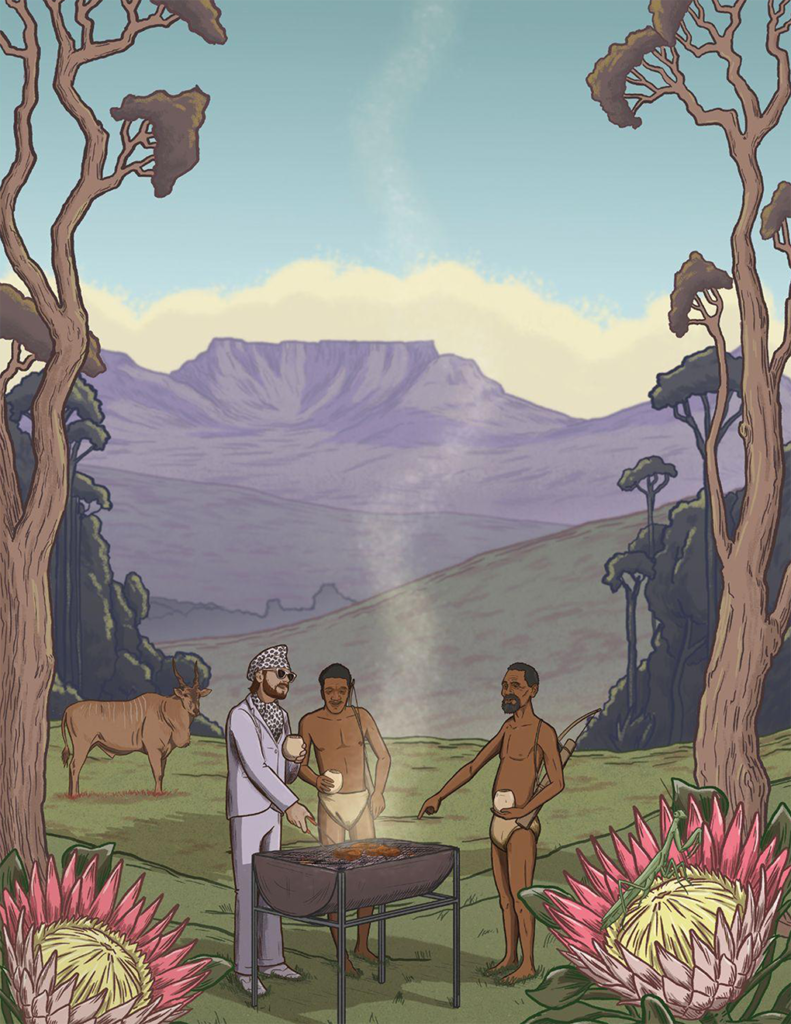

At the same time, my photography career was coming to an abrupt end and I was searching for the first next step. One day my friend Spoek Mathambo called me up and said that Nike wants to do a shoot with him, with a guy called Shawn Mortensen, who was the legendary photographer that did many of the famous portraits of Tupac. Since Spoek and myself both dabbled in music and visuals during the myspace era and came up with this idea around what we called Afro Sci-Fi he wanted me to help him create this whole world through production design and styling. So I made a bunch of outfits from what I could find at a cheap Chinese five rand store to keep the budget down. It was in this moment that I discovered this leopard print beanie and scarf and as I put it together on an outfit it resembled an African dictator. In a moment of fate, I was like “Fuck this is it. This is iconic.”

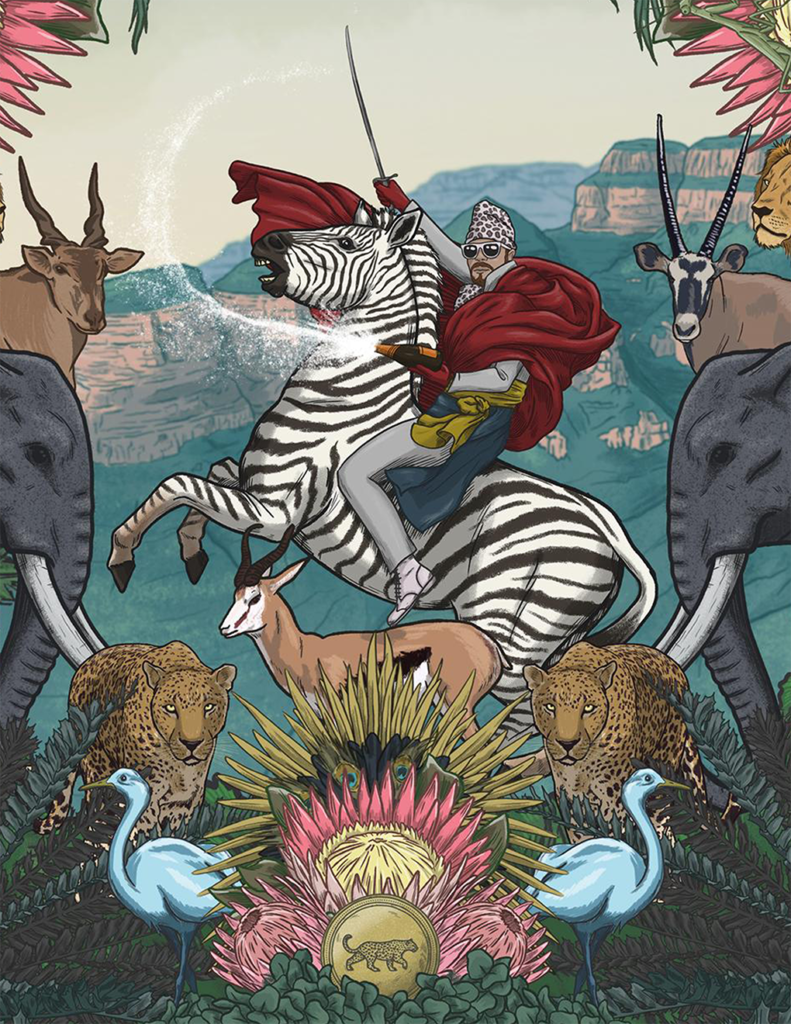

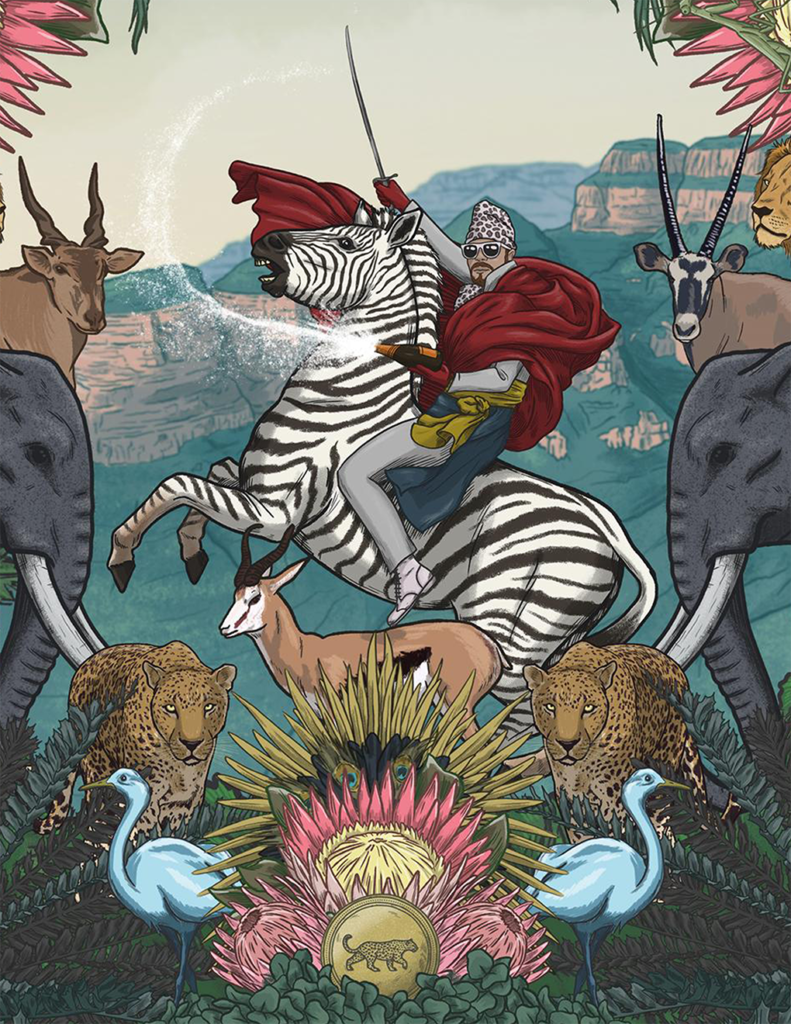

I threw myself into it following the same intuitive feeling that has driven most of my decision-making in life. The study started with the realisation that the image of the African Dictator was one of the greatest examples of how iconography had been used for power – even when it was so negative, it was very successful in convincing the world and a group of people. So I delved into the lives of Idi Amin Dada, Mobutu Sese Seko, and Muammar Gaddafi as my case studies.

The study started by looking into the lives of these different dictators and finding relationships between them, any similarities they shared throughout their histories. I found specific points that coincided in a mysterious pattern of actions, which I then distilled into a list of steps of how to create an icon out of a human being by these mechanics.

To me, it was a recipe, a great satire of how humans are fooled into believing in something. With the character of Gazelle, I decided to recreate each one of these happenings and document it through photography, video, and create something around it in the hope to reveal and understand these mechanics better.

What were the steps in this recipe?

The very first piece I made was taking the iconic outfit that sparked the idea, and creating ‘an official self-portrait’ that would be photographed, painted in oil, and published as far and wide as possible. An iconified image of sorts such as every politician, king, or emperor, had created to promote their ‘brand’ and set a course for influence. Few people realise in today’s world why a president’s portrait hangs in every state building.

While going through the sequence of the performance, I came across an obstacle. One of the steps was to create a discourse with the media and at that time there was no social media, only conventional channels like newspapers, TV, radio and magazines. If you wanted to be featured in any of these mediums you had to either be in business, politics, or culture. So I decided to use my previous dabbles in music and character as Gazelle, packaged as a pop music act, to start publicising a campaign around my manufactured icon.

Other steps dealt with the strategic iconography of performance in geographic locations. Just as politicians campaign strategically I created a performance around choosing a specific place in each province where something historically significant happened, and creating a self-portrait in that specific place as a series of images.

All of the documented outcomes became part of a satirical body of work titled, ‘The Status of Greatness’ that was shown in my first solo exhibition at WHATIFTHEWORLD gallery in Cape Town in 2009.

In the process leading up to that exhibition, I realised that it coincided with the political elections in South Africa, so I printed hundreds of political posters with my icon on them and placed them alongside other political parties on the streets in a satirical flex – I didn’t know it was actually illegal, super illegal. It’s like rigging an election but the ignorant act in retrospect felt like the perfect statement of how the power play of politics walks a thin line around ethics and what might be deemed legal.

On election day I created a performance where I would get a Mercedes Benz with flags on the front, bodyguards, and set up fake journalists at the entrance of the voting poll. Then I created a theatrical arrival, the officials would open the barricade for me to drive through since they thought it must be someone important. It was all fun and games unknowingly of the dangers of meddling in politics. During the years I created many public performances like these that I never published, just acting very intuitively, delving into the study through action.

Have there been any standout moments on your journey thus far?

The Status of Greatness was met with very different opinions. Some people were outraged that as a white person I could create anything in an African context or dare to explore anything to do with the history of colonialism, so they wrote pieces tearing the work apart without ever actually sitting down with me to explore where it all came from. ‘Selected Outrage’, as Chris Rock would say. Others were fascinated by how I could have an opinion on African politics. So it was not easy to throw oneself in the midst of controversy to let people break into conversation. But it made a mark and that is what I believe could bring value over time. Not long after the exhibition things exploded on the pop music front for the manufactured act Gazelle, so the proof of my exercise and study was in the pudding. You don’t know sometimes if you manifest something or if you are intuitively executing steps towards it, but the next thing I knew I was standing at Rocking the Daisies, which is one of the biggest festivals in South Africa, on a Friday night and I’m the main act – and I was like what the f…. just happened, ‘The Status of Greatness’ manifested into a figure with a real public voice. Whether people loved or hated what I had done one thing really matters to me, the bridges that I had built between different people from South Africa to create new narratives and evolve new cultures with no fear. A moment that I will cherish forever is when on of the biggest rappers in South African history, the late Ricky Rick came to me and shared, “…because of what you did with Gazelle, I didn’t want to be an American rapper anymore but wanted to express myself as a South African….” So whether people will ever accept me and my work remains a mystery to me but the words of this dear friend kept me going on the journey of creating things from a place of my own experience and truth.

Tell us about your experience in the music industry…

A wild, wild ride it was, meeting incredible people in places I never dreamt a kid from a farm in rural Limpopo would ever see. Europe welcomed me in a warm embrace and for years I bounced between nearly every country on the map. It was an incredibly enriching chapter in my life where I was able to bring people from so many different backgrounds together to create and connect. It truly felt like I was living my vocation of bringing different worlds together to create something new. But I became completely consumed by the life of the music industry. After moving to New York, I reassessed, reassembled and recalled what the origin of this experience was. It was then that I realised that I had been living a consecutive performance art piece spanning 10 years, manifesting the thesis that I once published as ‘The Status of Greatness’. With this realisation I felt the need to bring things full circle and softly kill Gazelle to move onto new chapters in my life.

In 2020 I was stranded in South Africa after a brief family visit, something called me to revive the character of Gazelle for another round after a hiatus of about 7 years. Not purely as a pop act but rather at an intersection of multiple mediums. The vision was to step back into the origin as a visual artist where I could create new bodies of work, who could still record and create songs, and also explore other avenues of design collaborations, all under one umbrella as a multidisciplinary artist.

Tell us a bit about your artistic intervention and live performance at the Faena Art’s Annual Gala 2022 late last year, what was that experience like?

In early 2022 while on a visit to Miami, I met up with Alan Faena and Ximena Caminos, the founders of Faena Arts, an arts foundation in America that has commissioned artists such as Damien Hirst. They shared that leading up to Art Basel that they were looking for an artist to create some kind of instillation and experience during their gala. I shared that I would love to submit an idea for their consideration and shared a premise right on the spot since I was always mesmerised by the incredibly grand Faena Forum where the happening would take place, so very intuitively visions started immediately flowing. I saw a big twenty-foot sculptural tower that would emit sounds and a grand ritual that would take place around it in an operatic stylised musical and choreographed dance experience. But it needed a depth of meaning, something that could bring greater value than just beauty if I had to dedicate a big part of my year to it.

I was fascinated with the idea that we as humans have so much more in common in our distant derived cultures than what separates us. The curiosity of how these identities or expressions evolve throughout history and how an idea or concept comes to us in the first place was something I had to explore.

The idea that one person could create a ritual of dancing around a fire in one part of the world and another doing exactly the same thing with no interaction proved that ideas might come to us from a collective consciousness. Or it might come through exchange that also influence a culture, wether positive or negative. Two people might exchange ideas that create value for one another, or someone might see something that inspires them to implement this same thing in their environment because they find purpose or beauty and sometimes even better what they find, or innovate something completely new. But then there is also the negative more destructive exchange of taking over what others have created, or exploitation others for their creations and becoming the beneficiary of their work. So it made me think about the ownership of what we deem culture, and the term cultural appropriation, since every culture that exists today is a culmination of different cultures colliding. So where would we draw the line of how we judge without becoming hypocritical.

Years before I was set up in an article by a journalist that never met me as a poster boy for cultural appropriation because I was a white South African creating art with an African aesthetic. What they did not understand perhaps was that I was the 10th generation born in Africa which makes who I am and what I express a bit more complicated. I like to think that rather than owning ideas or a culture we are custodians that celebrate or add to culture. We are conduits for ideas to flow through, and this is how culture have evolved since the beginning of time

I started looking at different cultural creations such as food, adornment, language or music, and follow their patterns to start creating the body of work which I would title ‘Patterns of Paradise’. If we would look at a musical instrument such as a guitar for example, there is a long evolution that spans the earth. A one-string instrument coming out of Africa goes on very different journeys. One part goes into North Africa to create the Kora, the other into Spain to become the guitar, then Asia to become the sitar, and across the Atlantic to North America to become and electric guitar. Imagine we refused this one string instrument not to evolve.

To explore this study as a white guy from Africa I knew would be daunting but necessary, since I could certainly be misunderstood because so many people in todays world immidiatily close their minds before seeing things as a whole. I’m not European, I’m not African, I’m not American, but I’m all of these through my heritage. So I thought let me find something in history that everyone knows that is an example of exactly that, and study it further and deeper. I came upon the origin story of why we speak different languages – the mythology of the tower of Babel; and I thought it could be a great story to base the work off because it exists in many religions and belief systems.

We’re in a similar time to Babel now, where we are individuals who believe we know best and that through what we are creating we are powerful as gods. Perhaps we are building this new tower of Babel through technology to take us beyond god and the divine, but at the same time, our culture is so strong that we all speak the same language. But something always comes in to destroy a unity between people with a seminal divide. We can see and feel it today, the extremes on either side of the spectrum. Conservatives with fear mongering nationalism making distressing statements, and liberals with with self righteous judgements and hypocritical wokeism, are but two of the polarizations of this divide – because both create the same action of dividing people and symbolically sending people in different directions of the earth to speak different languages as in the mythology of Babel.

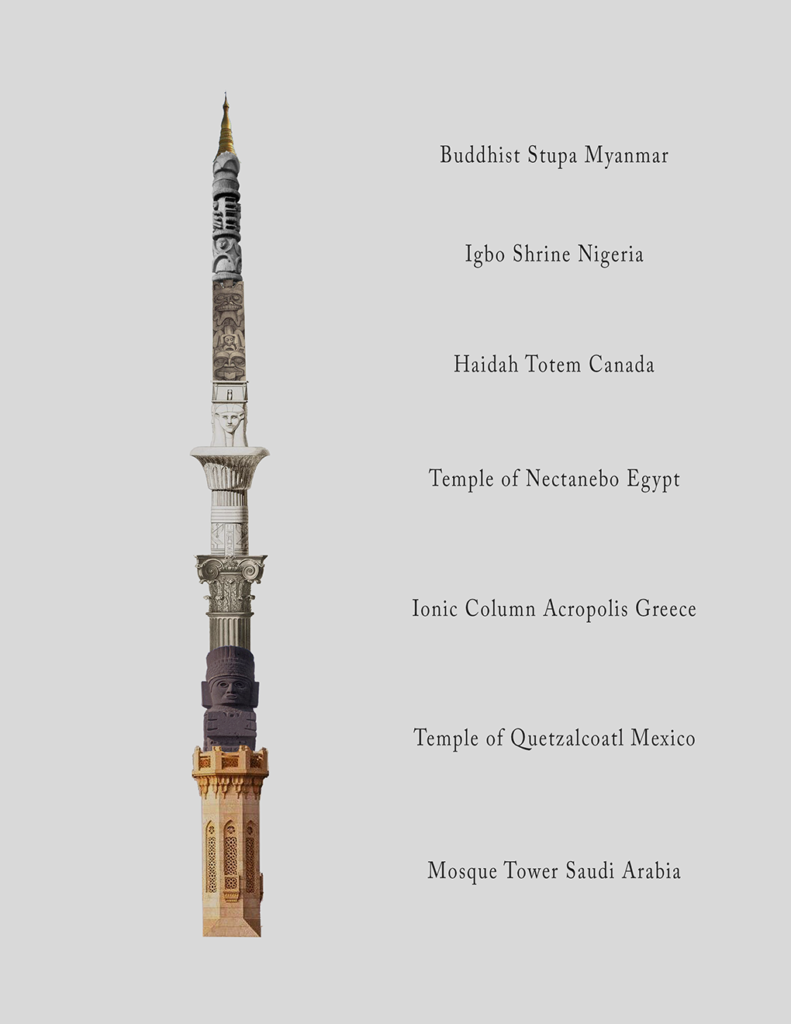

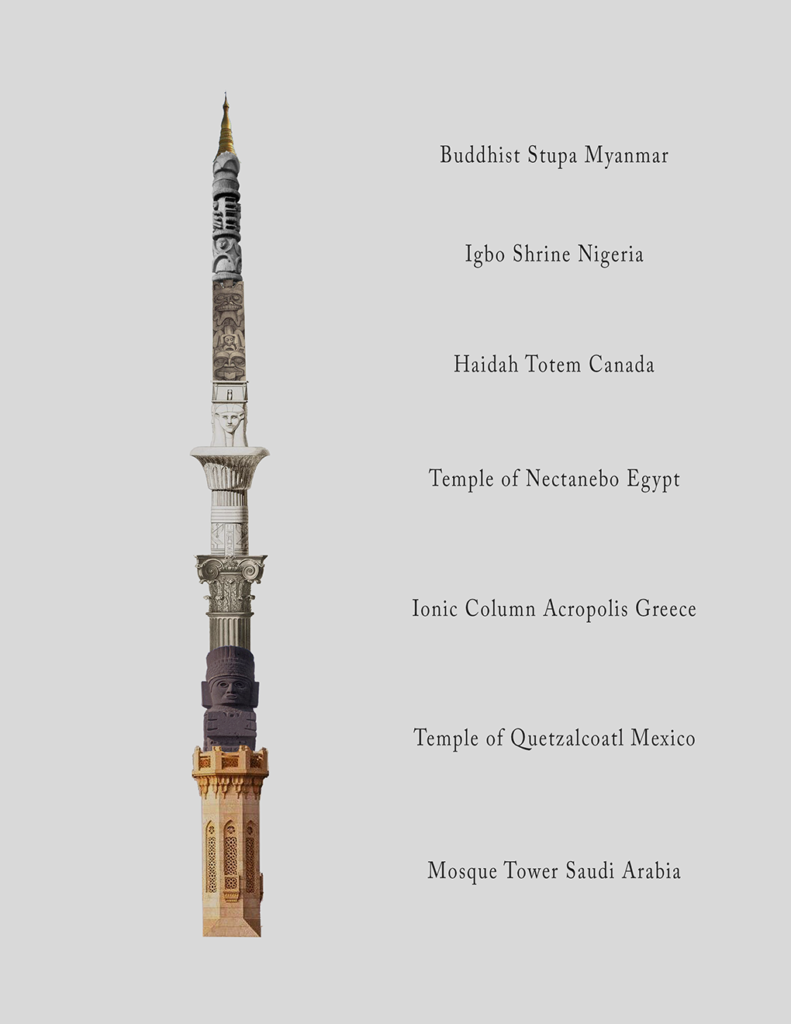

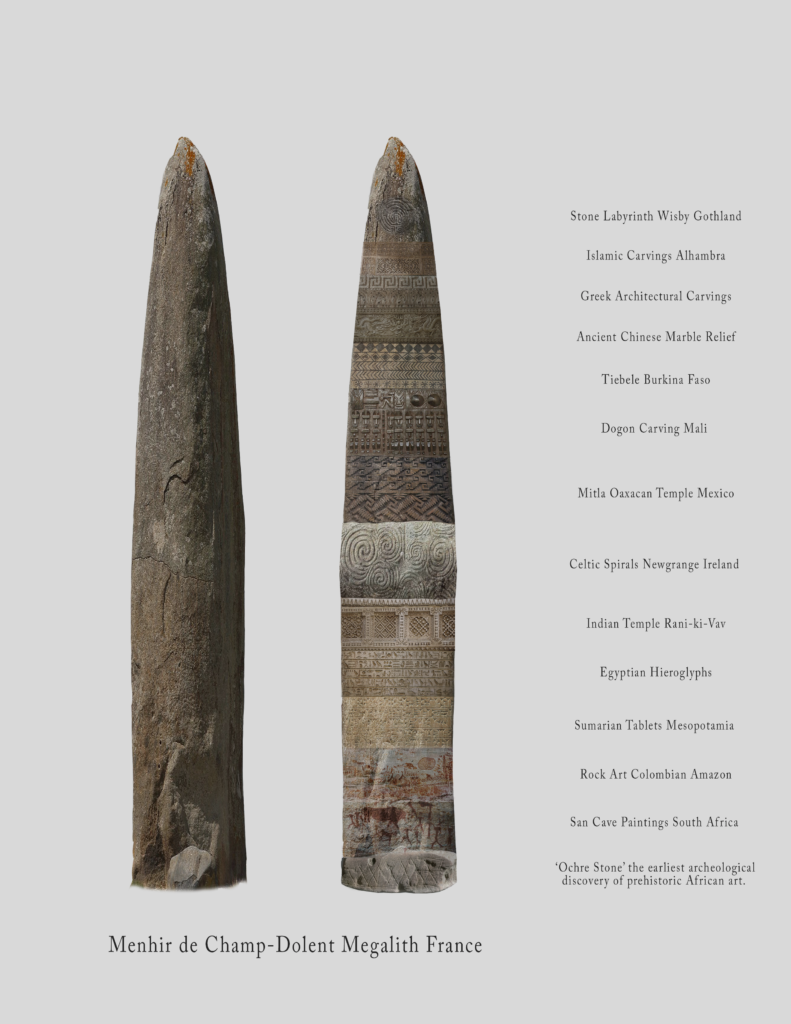

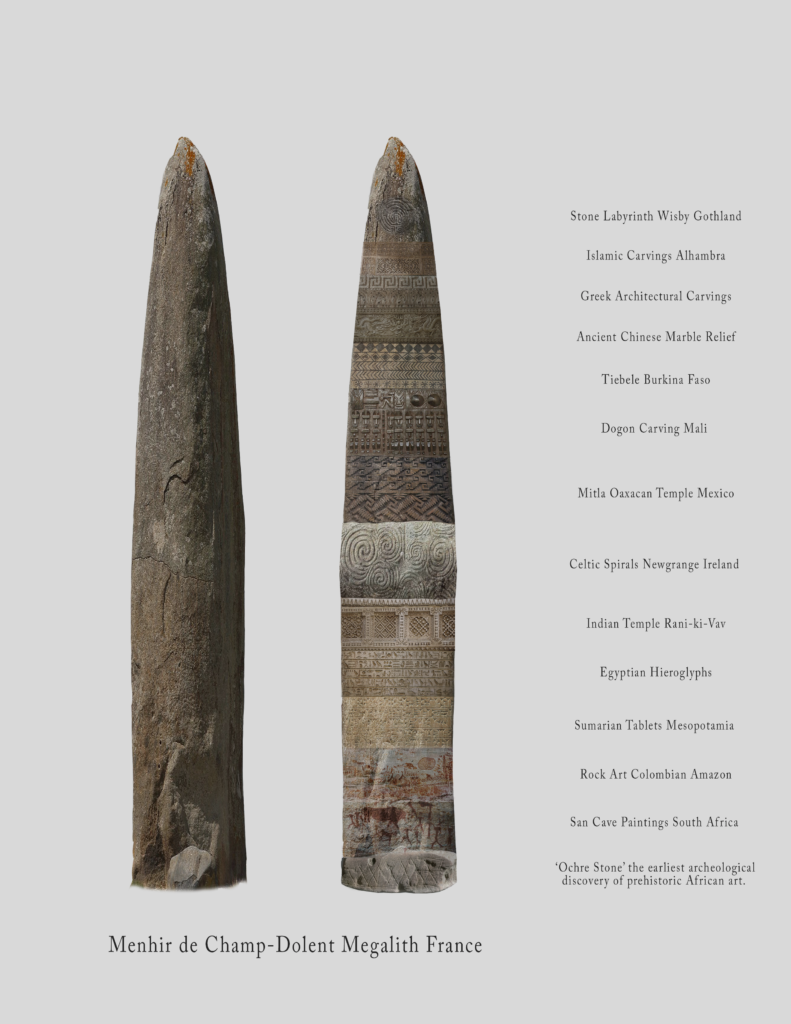

So, I thought it best to rebuild the tower of Babel as a ritual of remembrance to hopefully provoke thought on how our cultures are so intertwined. I approached this rebuilding by creating a tower out of important cultural objects spanning all continents and an anthropological study discovering the relationship between these objects that evolved alongside civilizations. Piecing them together in one object of beauty I hoped to show the striking relationships or common similarities between them. Culminating in a new object that carries multiple symbols of divinity, a new energetic center point that one could create a new ritual around, a ritual of remembrance.

In every belief system there is an energetic counterpoint also knows as an ‘Axis Mundi’. Wether it is a tribe that dances around a fire, a city with a great central monument, the towers of various temples, or a multitude of cultural totems, all become an energetic centre point which ritual is performed around. The Axis Mundi is believed to connect heaven or the divine, with earth or our reality, and the underworld which can represent a spirit world of sorts. We have so many similar spiritual practices deeply ingrained within us, that me might have lost the origin. I wanted to delve into this through Patterns of Paradise.

What do you want people to gain from your work?

My primary aim in my work is to provoke people’s curiosity and encourage them to ask questions. Nowadays, many people hold various opinions, yet they lack a deep understanding of history, including their own. By putting history into a larger context, I strive to create value in my profession. My ultimate goal is to bring people closer together by building a sense of community rather than driving them apart.

Mentors or artists you have learnt from?

I wish I had more mentors to be honest, I am making a conscious effort to ask for more advice from those who I admire these days. But then we can also learn in mentorship from those who we might not have met by studying their work and lives. I am certainly inspired by the school of artists that start with concept and express in a multitude of mediums such as Da Vinci, someone curious enough to not only express through art but truly delve into the philosophy and science of a subject. That is why I think Kentridge is so interesting. His expression in bringing theatre, socio-politics, and the experience of being human – all together in these different mediums. I love that because you shouldn’t be limited by what you do. It’s all part of the same thing, the same expression.

What advice would you give to artists trying to break into the industry?

Keep breaking with others. Because an industry is only made up of a group of people building together. I wish I had more humility and patience when I was younger, so that I could study under people that were on their way to create something great. I believe this age old tradition of mentorship is the surest way to find your feet in a very stable way. But sometimes your path can be more chaotic I guess. Another thought that sits with me is on the industry itself. Im not sure if art is only about being in the art world, having a gallery, and selling artworks. Yes, it helps to sustain a life, but then it can also be created by pure craft. To me, art is the study of something, a philosophy, and the use of expressing thoughts through mediums. Something that you are so interested by that you feel a form of obsession towards. An interest that you simply have to explore. I believe the creation of art is part of our evolution as humans, a way to better ourselves driven by interest and something that we find beautiful.

A continued build upon the vision of the icon, character and conceptual work that is Gazelle, Ferreira’s practice aims to spark conversation and reflection in a time where the line between truth and fiction is becoming evermore blurry. Exploring the socio-political and dealing with subjects such as history, culture and belonging, Ferreira’s work is an honest and uncompromising observation of our civilisation today.